In Go Figure, Carol Moldaw’s poems invite readers to draw their own conclusions. Observing, inquiring, and delving, Moldaw brings the intertwined strands of life and art to light at their most intimate, driven to understand and articulate the self in all its manifestations. Complex and inviting, with deft wit, the poems engage public and private life and voice a necessary and resounding affirmation of the feminine and of language emerging through silence.

Read the interview between Carol Moldaw and Sheng Yu below.

Sheng Yu: Your first poetry collection Taken From the River was published in 1993, and your latest collection Go Figure releases this year. This represents a very long period of writing and creative process. I am curious to know what drives your poetry writing.

Carol Moldaw: It’s just over 30 years since Taken from the River was published and I started writing poetry long before that. You’d think that I would understand what drives my writing after all this time, but it’s something I don’t spend much time thinking about. Writing poetry doesn’t come easily for me but it is essential to who I am.

SY: When did you start writing poetry? Why do you choose poetry as your main literary form?

CM: I don’t remember exactly, but like many children, I was drawn to nursery rhymes. I liked the repeating rhythms and rhymes and enjoyed playing—experimenting—with sound patterns. Then, when I started reading more poetry, in high school, I was drawn to the way poetry resonates emotionally and imaginatively through sound and image, and the possibilities, the levels, of its meanings. It seemed a way to express an inner self. To me, poetry is the heartbeat, the pulse. It combines so many means of expression; it’s tactile and sensory in its impact. Poetry suited my temperament.

SY: What expectations did your family have for your growth?

CM: My father had urged me to study economics in college, at Harvard, but I majored in American history and literature, taking as many poetry classes as possible. I also worked on a literary magazine that some friends of mine founded.

SY: What is the magazine about and how did it, and your college years, influence you?

CM: The magazine was called “Padan aram,” which is associated with the area (in the Bible) where Jacob wrestled with the angel. We published poetry, fiction, and photography. Padan aram was founded as an alternative to The Harvard Advocate, which had a venerable history, having published T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, and e.e. cummings, among others, as undergraduates. We sought to be fresh, contemporary, innovative. Rather than publishing Padan aram as a book or volume, we used a large newspaper format.

My college years were a time of exploration and creativity. The transition from California to Boston, was a culture shock for me. I felt ignorant. I was taught American history from a different vantage point, growing up in the West, but Boston is the cradle of the United States, or sees itself that way. I was alienated at first and also found it gray and claustrophobic. I didn’t know anyone there. But eventually I adjusted, started meeting poets, making friends, and orienting myself. The most important teacher I had in college was Robert Fitzgerald, who was himself a poet, though best known for translating The Iliad and The Odyssey. He taught a class in prosody that was foundational for me.

SY: I would like to know what the poetry scene was like in Boston at that time.

CM: A number of poets came to read at Harvard while I was there: Seamus Heaney, James Merrill, Adrienne Rich, Robert Creeley, and David Shapiro (who was part of the New York scene) are among the more memorable poets I heard read. Aside from that, I didn’t have a lot of interaction with poets outside of the university. Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, both influential poets, both taught at Harvard for some of the time I was there. I didn’t study with Robert Lowell but took a wonderful small reading seminar with Elizabeth Bishop. Her work remains significant to me.

SY: Compared to when you first started publishing, do you still have the same writing habits (I mean, focus) today? When reading your latest collection of poems, I got a strong sense of introspection—it seems like you are beginning to reexamine and re-understand yourself; and an outward focus—everything in life is given life through your poetry; more meditation; and your simple life, yet full of tension—“This morning, last night: / aggravation, desire: / two different orders of dirty looks.” In your arguments and reconciliations with yourself in every moment, I feel an increasingly profound contemplation of the state of life; as well as inevitable memories, fragmented recollections, your emotions have become softer and more reconciled. Can I describe it like this? It seems inward, but it’s actually more outward, towards life.

CM: I appreciate your close reading and understanding of my work. I do think that my poems are increasingly concerned with introspection and attempts to understand oneself. At the same time, I’ve learned that this doesn’t take place in a vacuum, and I think I engage with the world in my work more than I did when I started out. Maybe some people become more didactic as they get older, but I notice that in my work I’ve become more open to ambiguities, nuances, paradoxes, ironies, and open-endedness.

For me, one aspect of writing poetry is the working out of questions, but they aren’t questions I pre-formulate. In writing a poem I discover what questions are on the edges of my consciousness and what questions matter to me. The poem doesn’t necessarily provide answers to these questions; it provides a lens, a way of exploring and focusing.

SY: I’m wondering whether it’s accurate to assert that there exists an ultimate question that you wish to deeply explore or dig into about the existence of the world.

CM: Writing poems, I engage with questions large and small. I find that questions about existence posed as specifics yield more, have deeper impact, than “ultimate” questions which, in their abstractness, can feel far removed. For instance, in “A Measure,” the question is whether the dying and the newly dead are still aware of the living. Where does their spirit reside? How long do they linger near us? The poem is placed at my father’s deathbed with the rabbi chanting prayers, his family around him. The question of what he hears, what he is aware of, how long his spirit lingers, takes on a personal significance which all of us can feel.

For me, one aspect of writing poetry is the working out of questions, but they aren’t questions I pre-formulate. In writing a poem I discover what questions are on the edges of my consciousness and what questions matter to me. The poem doesn’t necessarily provide answers to these questions; it provides a lens, a way of exploring and focusing.

SY: Could you share with us some stories about your connection to your Jewish tradition? You often reference Jewish and other religious images in some of your works. For example, in the poem “Lines Begun on Yom Kippur,” when “the long and short piercing blasts of the shofar” sound, I feel as if I am following the narrator to the roadside synagogue.

CM: Well, the shofar is sounded every year at the end of the High Holy Days, and that sound, which signifies the “sealing of the book of life” for the coming year, has always powerfully affected me. It is resonant and piercing. My identity as a Jew is deep-rooted but I’m not particularly religious. Being Jewish is simply part of who I am. I was brought up with a code of ethics and a tradition of social justice that I strongly associate with Judaism.

SY: In your latest writings, I sense a kind of joy that belongs to spiritual enlightenment, especially when I read a sentence like “until an onrush bellows / a mindless heartless ecstasy / through the empty sack of me.” What were you thinking at that moment? What interesting insights do you have about life at this moment?

CM: I think any interesting insights I have about life are expressed in the poems! The poem you quote from, “Meditation in the Open-Air Garage,” came from the experience of meditating and listening to the wind, which can be strong where we live. We are fortunate to have many trees around us: cottonwood, aspen, willow, apple, box elder, and I find it moving to listen to the different sounds the different kinds of leaves make in the wind. The lines you quote were as close as I could get to imagining and articulating myself as a leaf in an onrush of wind.

SY: After reading your poetry collections, I can feel that each collection has its own unique creative focus. Reading them feels like embarking on different adventures at different times, and I can sense the changes in your state of mind. Is there a connection between the original intentions behind each of your collections?

CM: It is my inclination and my practice to let preoccupations—thematic and poetic—come through to consciousness as part of the writing process. There is a place for intentionality, but for me it can be stifling if it is too strong too soon. I put most of my intentionality into my craft, my technique, using my inner tuning fork, but what gets expressed needs to come from a deeper place than a conscious intent. My books are connected by my growth as a person and as an artist.

SY: In your poetry, as I have mentioned before, I sense a form of “healing”—the narrator’s healing of the poet, and the poet’s healing of the reader. Many times, they have helped me, as a woman, to soothe my scars. Speaking of the age-old topic of the function of poetry, I believe a pioneering aspect of your poetry is the implicit functionality it carries. In a world of seemingly meaningless postmodern poetry “ruins” and games, I perceive an immensely precious love and compassion for human life in your work. Do you consider these functions when creating your work, or is this kind of influence something you anticipate?

CM: I never would have predicted that anyone would find a functionality in my poetry—what an unexpected compliment and delight! While I’m writing I don’t let myself think about whether anyone else will find what I’m writing meaningful—it needs to be enough that working on whatever poem is at hand has meaning to me. It’s a bit of a paradox: I write them for myself but I don’t want them to be only for myself. I do hope that my poems open up avenues of thought and feeling for others, that they resonate deeply. Poems, at their best, work in ways mysterious and profound, and if any of my poems operate on that level, I will have made a contribution I’m proud of.

SY: As a creative writing teacher, you have taught at various institutions such as Naropa University and the College of Santa Fe. I am very curious to know about your approach to teaching poetry writing. Any special or unforgettable stories with your students?

CM: Right now, I have a small handful of private students who I work with individually and this is actually the way that I prefer to teach. I like to read poems closely and to help people find and expand the poetic that suits them individually. One woman I’ve been working with for a number of years, Radha Marcum, has been writing astonishing and subtle poems that engage with environmental degradation, among other things. Her second book, pine soot tendon bone, won The Washington Prize and was just published by The Word Works Press.

SY: Although I really don’t want to add the title “female poet” to your name, I have to say that the change in female consciousness is something I deeply feel when translating your work. Whether as a participant in an emotional relationship, a daughter, a wife, and of course, a mother, as your identity changes, the objects of your lyricism and your concerns are also changing. I particularly like a comment on your poetry, “a kind of gentle yet completely certain subtle lyricism.”The special nature of being a woman invites me back to your poetry time and again, to be confused, pained, or joyful with the narrator. Do you enjoy this sense of change?

CM: Some American women poets in the 20th century, such as Elizabeth Bishop, didn’t want to be considered as “female poets” because they felt the term created a ghettoization and belittled their achievement. I see my work as coming out of a braiding of different lineages, and an important one of these strands is certainly a lineage of female poets and female consciousness. I enjoy not feeling conflicted about being a woman or a woman poet.

I am definitely a feminist. Feminism is a necessary corrective to a severe power imbalance. In different ways across the globe, women are in peril. But when I say I write as a woman, I mean something else. I don’t write poetry with an agenda or as propaganda, but I have always felt that my writing is allied with, stems from, a distinctly female point of view.

SY: I would like to hear your thoughts on feminism in your work. I feel in your poetry that you want to speak out and express things as a woman for women.

CM: I am definitely a feminist. Feminism is a necessary corrective to a severe power imbalance. In different ways across the globe, women are in peril. But when I say I write as a woman, I mean something else. I don’t write poetry with an agenda or as propaganda, but I have always felt that my writing is allied with, stems from, a distinctly female point of view, not a gender- neutral point of view. Men might think they write gender-neutral work, but they often are just taking their gender as the measure of the world. I’m very pleased when I hear that my work resonates with women.

SY: I think “Beauty, Refracted” is a very unique poem. You have created “Beauty” as a

character from a fairy tale, but every action of hers is refracted onto us, and there’s the humorous yet eerie circus. You open with a quote from The Feminine in Fairytale, “Every dark thing one falls into can be called an initiation,” and the adult world in fairy tales has a stronger sense of contrast and tearing, a Heterotopia? Why did you create such a fairy tale poem? I believe that after readers have finished, they will have a completely new understanding of the title Beauty Refracted.

CM: While the title of the book is Beauty Refracted, the poem is “Beauty, Refracted”—with a comma between the words (as you correctly had it). I wanted the book title to reflect the idea that each poem was a separate refraction, or instance, of beauty. I hoped that inserting a comma into the poem title would suggest Beauty as a proper noun, a particular being, Sleeping Beauty, whose experience is being refracted through the lens of the poem’s different sections. In creating a fairy tale poem, I was greatly influenced by Marie-Louis von Franz’s The Feminine in Fairy Tales, which provides the epigraph. Franz’s book is one I’ve gone back to many times over the years, and it has been a source of self-understanding as well as that of feminine psychology in general. My use of fairy tale was a way to cast the content of the poem in a more archetypal light, as opposed to having it read as a chronicle of idiosyncratic individual experience. I wanted the poem to contain both the whimsy and gravity of childhood, which I think fairy tales do.

SY: The poem “Another Part of the Field (hexagrams)” is very interesting, and it’s the first time I’ve read a poet from outside of China systematically creating poetry inspired by the I Ching. You mentioned that each six-line poem was inspired by one of the hexagrams of the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes——when reading these verses, I saw the ups and downs of emotions, observed change, and also found moments of poets’ return and resignation. You skillfully and unexpectedly employed various images and rhythmic lines, creating a very interesting experiment in the blending of Eastern and Western cultures. Could you explain the original intention behind the creation and the process of composing this poem?

CM: I had read the I Ching and cast hexagrams using Chinese coins for many years before I wrote “Another Part of the Field.” I always found it extremely thought-provoking and helpful.

The translation I know best, and the one I used in writing the poem, is the English version translated by Cary Baynes from Richard Wilhelm’s German translation—perhaps that makes it a bit thirdhand. When I first started to think about writing a poem based on the I Ching, I couldn’t

quite see how to do it. The I Ching’s universality and wisdom were intimidating. And I certainly didn’t want to paraphrase what was already poetically rich and imagistic.

Eventually, at a time when I was frustrated with the way my writing was going, I started to use the I Ching to loosen up. I wasn’t thinking, when I started, of a long poem; I just wanted to use a hexagram at a time to free my unconscious. I would toss the coins as soon as I got to my study and then would write whatever the hexagram I’d received brought to mind. I liked that I never knew ahead of time which one I would get or how I would relate to it. I grew to find that by focusing on the small moment I was able to work with the I Ching’s ancient and vast truths. The landscape became localized; the “superior man” and the “inferior man” became myself.

After a few days of tossing the coins followed by immediate writing, I realized that I wanted to shape each day’s writing into a succinct poetic structure, something like a haiku, but one that would have relevance to the tradition of the I Ching. I invented a form, which I called a hexagram: six lines, in reference to the I Ching’s six-line hexagrams; each having (in English) three beats or strong stresses, in reference to the three coins. I loved the interaction of the text, my unconscious, and the shaped writing. I wrote these almost every day for two years, even as I began to work on other poems. At the end, I kept the best ones and arranged them into a seasonal sequence. As you noted, they encompass many ups and downs of mood, shiftings of location and consciousness. The I Ching proved, unsurprisingly, an endless resource and inspiration.

SY: What interests me greatly in Beauty Refracted is the “loop” series of poetry. I can see the different perceptions of moments in various places, the overlap of reality and illusion, and of course, your experiences in the loop of immersion in dreams — the leaping imagery intertwines various emotions such as agony, tedium, despair, joy, and hope. Particularly, when I read “night’s grief unstaunchable— / my father barefoot in snow,” a powerful emotional resonance struck me. These “loop” poems are quite exceptional, and I would love to hear about your thoughts and intentions in creating them.

CM: The “loop” poems were inspired by walking, by the kind of walk that doesn’t have a destination but is for walking’s sake. Initially, I wanted to remember and record the thoughts I’d had while walking and the poems I sometimes began to compose in my head. Then I wanted to create poems that worked with the thoughts and the walk together. The dreams seemed to me analogous to walks, or the dream-thoughts analogous to walking-thoughts. And one image I had while in a car, near home, seemed to fit, so I made room for that slight deviation.

SY: Have you ever attended art events or collaborated with artists on poetry installation exhibitions?

CM: I find visual art inspiring and have written a number of poems inspired by painting and art installations. “The Lightning Field” takes its name from and is inspired by Walter de Maria’s land art. Go Figure includes “Painter and Muse (I),” an ekphrastic poem inspired by a painting of Lucien Freud’s. I’ve only collaborated with one artist though, a quilter. We were commissioned to work together without knowing anything about each other or our work. Through correspondence, we discovered that we were both huge admirers of the work of the painter Agnes Martin. I also quizzed her on quilting techniques and language. What resulted was my poem “Quilted Pantoum,” which utilizes both quilting language and phrases from a book Agnes Martin wrote about her aesthetic philosophy. The quilter made a free-floating quilt inspired by Martin’s work and printed my poem on it. SY: Have other forms of art influenced your work? I noticed that the front pages of your books are very beautiful.

SY: Have other forms of art influenced your work? I noticed that the front pages of your books are very beautiful.

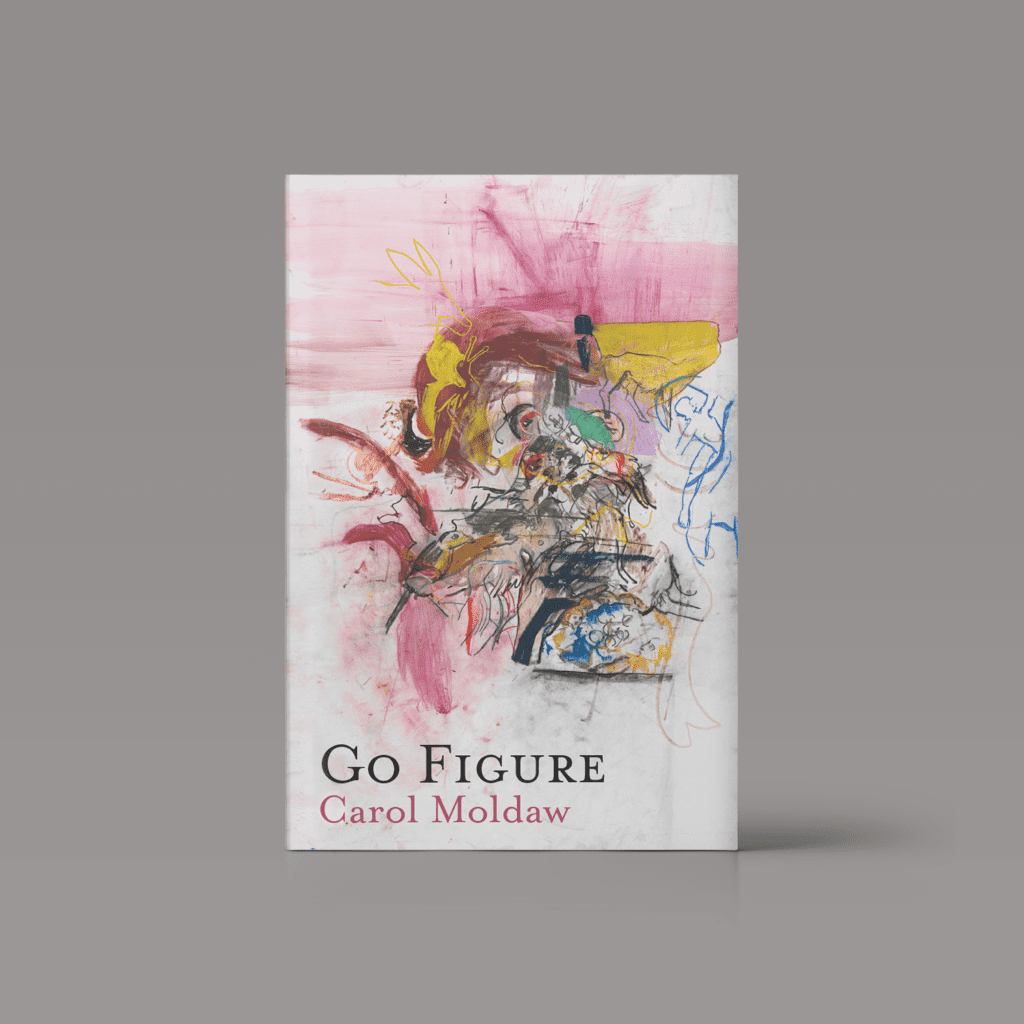

CM: Thank you! Being able to pick the art image for the covers of each of my books has meant a lot to me. The watercolor-gouache on the cover of Go Figure is by Cecily Brown and it moves me deeply, as if it were made for me.

Poetry itself has influenced my work. Whether I’m rereading a poem that I know well and love, or reading a poem I’ve just come across and am struck by, poetry is a continual wellspring of inspiration.

SY: What are your expectations for poetry?

CM: My first expectation for poetry is that its language be unadulterated and uncorrupted. Or, that if linguistic corruptions are used, they are used consciously—knowingly and critically. I want poetry to give me linguistic pleasure and any kind of insight. At the same time, I prefer poetry that gives me room to draw my own conclusions. I don’t like everything spelled out.

Carol Moldaw is the author of six previous books of poetry. She has received a Merwin

Conservancy Artists Residency, a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing

Fellowship, a Lannan Foundation Residency Fellowship, and a Pushcart Prize. Her writing has appeared widely in such journals as The American Poetry Review, The Georgia Review, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, Poetry, and The Yale Review, as well as many anthologies. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Dr. Sheng Yu is a lecturer and translator in the Department of Foreign Languages at the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. She is also the translator of Carol Moldaw’s upcoming poetry collection in Chinese.