by David Roediger

Note: The author’s lecture tour for An Ordinary White begins March 6 at the University of Kansas, with events later in the month at the University of Oregon (March 11), Lewis and Clark (March 13), Urbana-Champaign (March 27), and Logan Community College (March 31). More events and talks will be announced soon!

I finally did pick up art appreciation, not just art history, especially for the paintings of Penelope Rosemont, the drawings of Franklin, and the creative energy of such Chicago surrealists as Robert Green, Gail Ahrens, Joel Williams, Tamara Smith, and Beth and Paul Garon. Intellectually I became fascinated by the surrealist concept of miserabilism, the idea that widespread addiction to miserable social relations, to planet-killing development strategies, to overwork, and to debt underpins how rulers rule.

The national and even global range of the surrealist group’s contacts was daunting. My kids came to know the African American beat and surrealist poet Ted Joans (who like me was partly from Cairo, Illinois) as well as such brilliant artists, musicians, and writers as Jayne Cortez, Laura Corsiglia, Philip Lamantia, Leonora Carrington, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. At the time the kids much preferred the Rosemonts’ house, stuffed with old comics, with toys and gadgets as well as art, to holding meetings at our house. A resident laughing thrush who sometimes talked on the phone, or at least raucously kept others from doing so, completed the scene and soundtrack at their place.

The national and even global range of the surrealist group’s contacts was daunting. My kids came to know the African American beat and surrealist poet Ted Joans (who like me was partly from Cairo, Illinois) as well as such brilliant artists, musicians, and writers as Jayne Cortez, Laura Corsiglia, Philip Lamantia, Leonora Carrington, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. At the time the kids much preferred the Rosemonts’ house, stuffed with old comics, with toys and gadgets as well as art, to holding meetings at our house. A resident laughing thrush who sometimes talked on the phone, or at least raucously kept others from doing so, completed the scene and soundtrack at their place.

The arena in which I came to know the Rosemonts best turned out to be a central focus of my activity over the next twenty-five years: that of attempting to reach a broad US left through books from the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company. I knew of the Kerr Company vaguely even before arriving in Chicago. In the Dekalb study group where I learned about historical materialism when we read classic short works by Marx, Lenin, and Engels we occasionally splurged on classic editions published by Kerr, still inexpensive and much better-looking than the cheap China Books editions. The press’s edition of the Communist Manifesto was a staple on the US left and we sometimes used Kerr’s pamphlet editions of Wage-Labor and Capital and Value, Price, and Profit. Much more legendary than these was the Kerr edition of all three volumes of Marx’s Capital, the authoritative English translation until at least the 1960s, having originally appeared in handsome hardbound volumes published between 1906 and 1909. It was still the edition most cited by historians when I entered Northwestern. In Dekalb I knew I should read those volumes, and at Red Rose, with time on my hands, I did so—well the first two anyhow.

Charles Hope Kerr, from Georgia, had founded the company that bore his name in 1886 as a progressive Unitarian publisher. By the mid-1890s the populist movement for farmer-labor unity dragged Kerr and the company to the left and shortly thereafter the company entered its distinctly socialist stage with the inauguration of its 60-pamphlet “Pocket Library of Socialism.” The first title in the series, a socialist-feminist pamphlet by May Walden Kerr, appeared in 1899. Kerr’s International Socialist Review (ISR) debuted in 1900 and soon became a leading English-language organ of the leftwing of socialist thought and language, famed far beyond the US. The company issued shares pitched to supporters, not to investors, and indeed promised to never pay a dividend, offering instead only discounts on literature and a feeling of having advanced the coming of the “cooperative commonwealth.”

The company issued shares pitched to supporters, not to investors, and indeed promised to never pay a dividend, offering instead only discounts on literature and a feeling of having advanced the coming of the “cooperative commonwealth.”

World War One, and the opposition of the best of the socialist movement to it, halted the company’s rise. Both the US and Canadian authorities revoked the mailing privileges of ISR and the red scares following the war decimated the base of US radicalism even as the much of remaining left re-oriented towards the Soviet Revolution. The political and the financial intertwined with the personal, most notably in the case of the 1922 suicide of the most talented intellectual associated with Kerr, Mary Marcy. In the 1920s Charles Hope Kerr sold shares in the enterprise bearing his name to members of the Proletarian Party (PP), a dissenting US faction of the Communist International growing out of the Michigan Socialist Party. John Keracher, a PPer, had already been doing day-to-day Kerr work before the transfer.

The new PP leadership proved apt custodians for a nearly undermined Kerr Company. Their activities as a party focused on education among a base of primarily skilled workers. They kept the Marxist classics in print, adding sparingly, for example with Keracher’s own excellent 1935 short work on psychology, advertising, and capitalism, The Head-Fixing Industry. In 1971, as the party lost its aging members, the PP turned Kerr over to a group of veteran Chicago radicals including the Industrial Workers of the World historian and editor Fred Thompson, the former labor defense activist and left opera critic (turned economics professor) Joe Giganti, the Korean War resister Burt Rosen, and the writer on Indigenous peoples Virgil Vogel. Publishing for, or in cooperation with, the Illinois Labor History Society (ILHS) gave the reorganized company some resources. Even so, the average age of that excellent, reconstituted group was itself very high. Thompson himself recalled to me that his goal in signing on did not exceed providing a “decent burial” to a venerable institution.

However, the new leadership quickly produced a new edition of the wonderful The Autobiography of Mother Jones, a Kerr book since the 1920s. Completely new titles emerged, including Carolyn Ashbaugh’s groundbreaking Lucy Parsons: American Revolutionary and Daniel Fusfeld’s Rise & Repression of Radical Labor, (a well-timed short guide to workers’ movements and state violence. Kerr showed signs of being back in business, though the successes were uneven and themselves created more work than the board could handle. The West Loop office was inconvenient and filling orders at the post office was grueling. My first visit to Kerr was perhaps in 1978, precisely to carry things and generally help out. My lasting memory of the working visit is of countless boxes of Bernard Brommel’s just off-the-press biography of Eugene Victor Debs, a solid work but one even I knew could not sell in the vast quantities that had been printed and bound in hardcover. The board itself soon realized the need for assistance, adding the Rosemonts, and then me. By my late 20s I had my dream job, however unpaid.

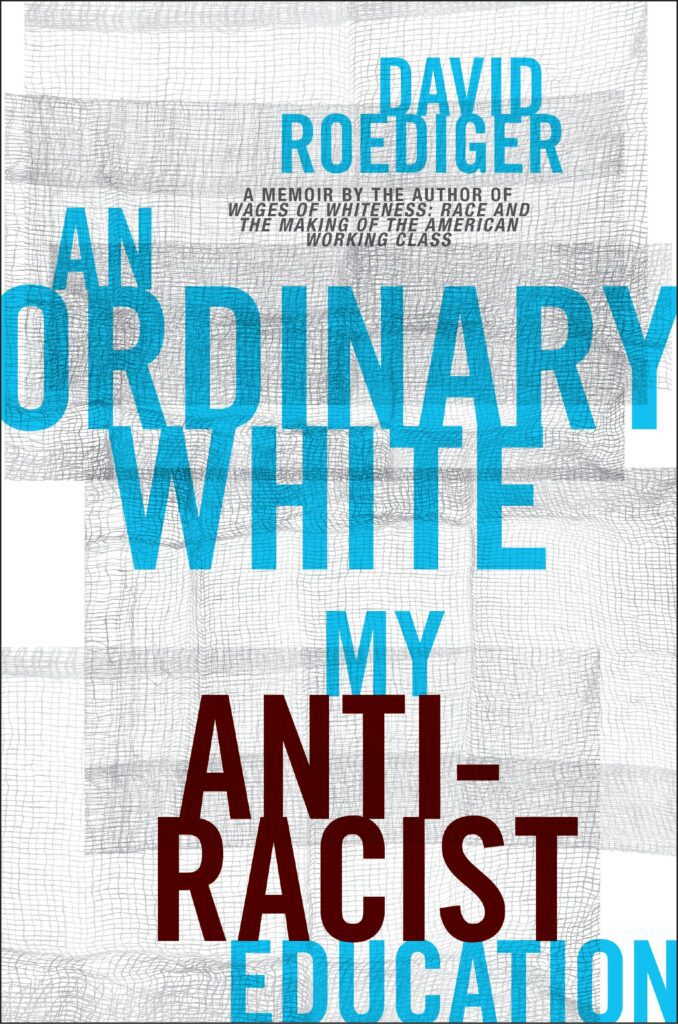

Excerpted from An Ordinary White: My Antiracist Education by David Roediger. Copyright © 2025. Available from Fordham University Press.

David Roediger is Foundation Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at University of Kansas. His books include The Wages of Whiteness (Verso, 1991), which won the Merle Curti Award from the Organization of American Historians and Class, Race and Marxism (Verso, 2017), which won the Working Class Studies Association’s C.L.R. James Award.