By Lary Bloom

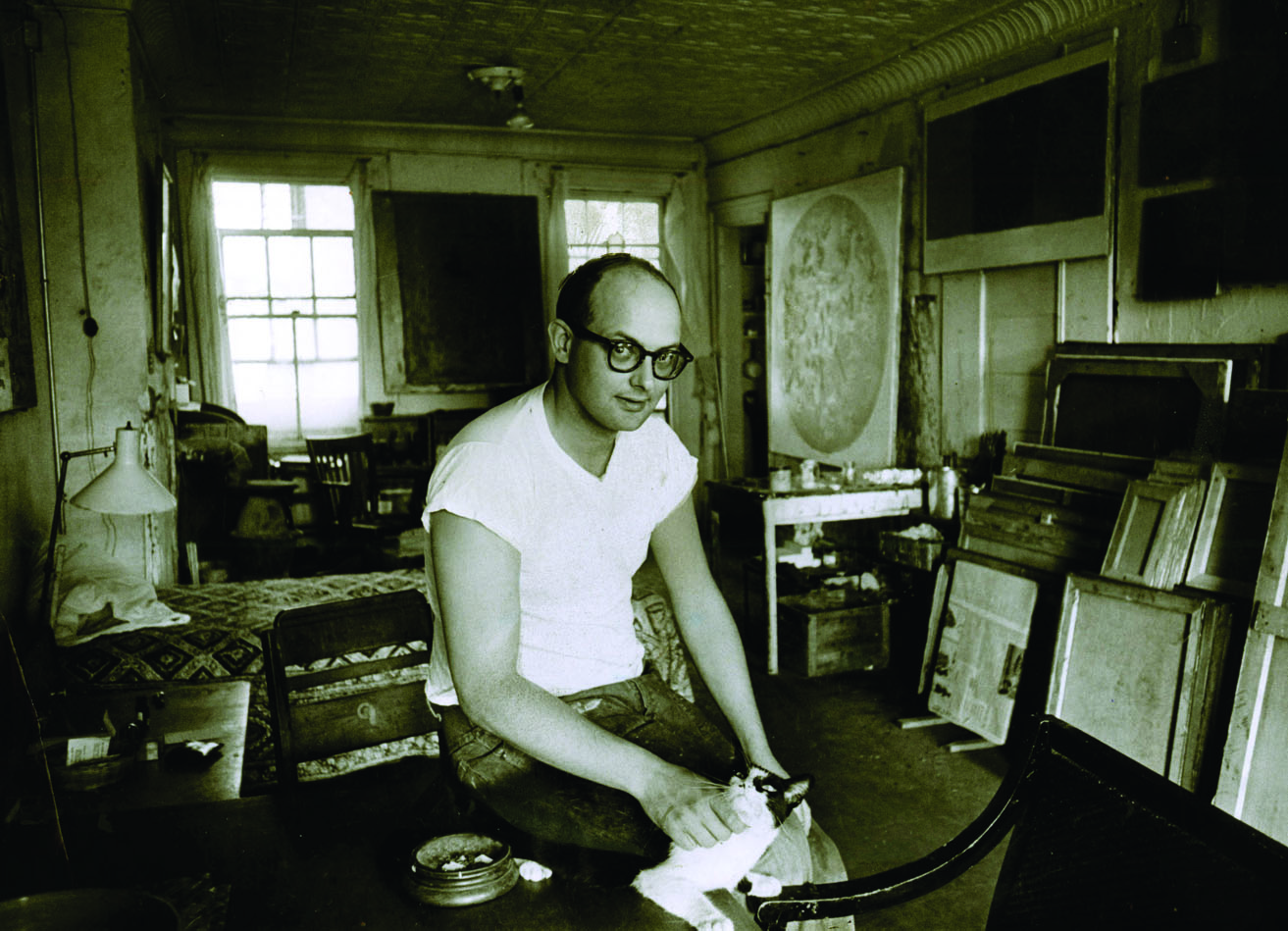

Fifty years ago, Sol LeWitt published his second manifesto, further upending centuries-old assumptions about how art is made. The effect of “Sentences on Conceptual Art” was minimal at the time, as LeWitt and his circle of rebels were dismissed by influential critics, and their practices had yet to spread much beyond the Lower East Side where they lived (in many cases, as with LeWitt, illegally).

His worked showed that, as he was seldom involved with physical installations, leaving that to his crew chiefs and the thousands of young artists he hired over the decades. But it also became central to the installations themselves.

For example, just a few years before he died in 2007, he explained to me that he was asked to do a site-specific installation at an abandoned synagogue in Stommeln, one of the few in the country that hadn’t been destroyed by the Nazis, but which in recent years had been home only to art installations.

His idea was not traditional art at all. That is, no painting, no sculpture, no physical element except for one crude construction: a brick wall. The wall was to be placed inside the entrance, fulling blocking the sanctuary from view. But though visitors to the exhibition would not be able to see what’s inside, they could hear voices. These were the recorded “Lost Voices” of German Jews praying, which I translated from Hebrew into English, along with our friend Reuven Clein. So, the effect was to demonstrate a strong sense of humanity inside, even if it was in the form of ghosts reciting liturgy.

Indeed, the project demonstrated LeWitt’s commitment to the end of his career of what he argued in “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” – that art can be art even if never becomes a physical manifestation and that for artists, “Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically,” that “bad ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution,” and that “It’s hard to bungle a good idea.”

Thus, he amplified what he had written two years earlier, in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” published in Artforum. LeWitt had focused on inception and inspiration rather than what happens afterward. “The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.” The physical creation of the art, he said, is “perfunctory.” In this, he saw his role similar to that of a composer or architect whose work is largely done when the score or drawing is finished, leaving the completion to others.

In “Paragraphs,” his opening salvo challenged conventional thinking of the time, and challenged his peers to seek their own truths rather than the ones defined by critics or market trends: “The editor has written me that he is in favor of avoiding the ‘notion that the artist is a kind of ape that has to be explained by the civilized critic’ This should be good news to both artists and apes.” And he held the view that critics use a secret language meant to impress each other and bamboozle the public. (“Reading art criticism is like chewing glass,” he said.)

LeWitt wrote “Sentences” in 1969 around the time Paula Cooper, a pioneer in SoHo, produced her first show.

LeWitt used “Sentences” to clarify points made in “Paragraphs” and further push the view that artists, far from being fringe societal figures whose talent is expressed by disciplined hands, can do their best work when hands become irrelevant.

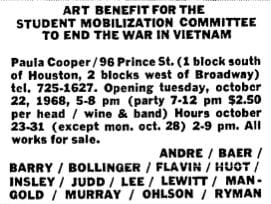

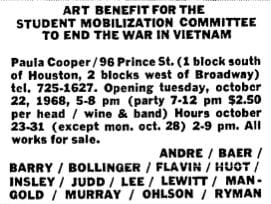

LeWitt wrote “Sentences” around the time Paula Cooper, a pioneer in SoHo, produced her first show at her gallery with the assistance of Lucy R. Lippard, who as a writer on contemporary art that had championed the LeWitt circle. Fourteen artists were chosen to participate in the “Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.” Aside from LeWitt and Andre, others selected included Dan Flavin, Robert Ryman, Robert Mangold, Donald Judd and the lone woman, Jo Baer.

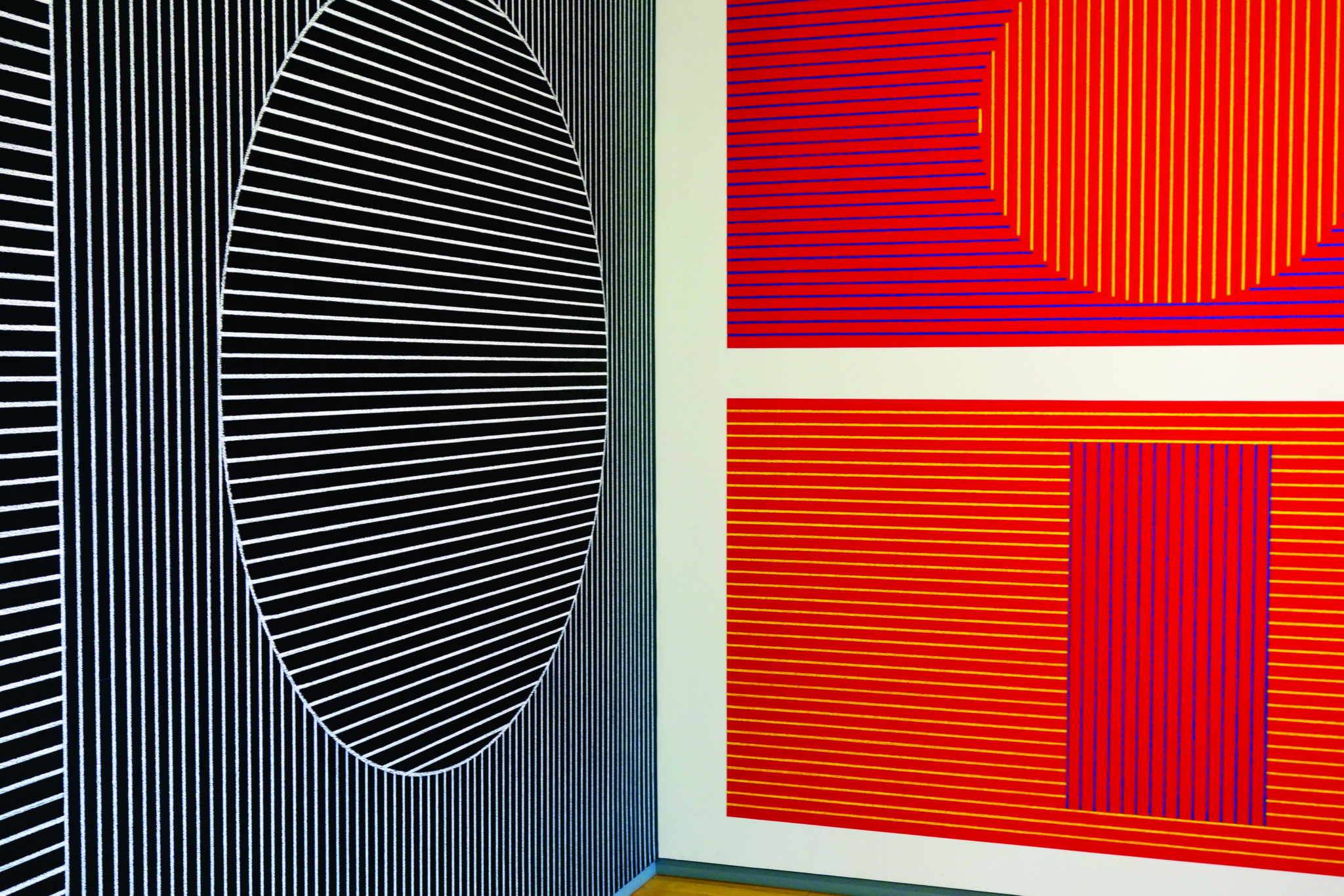

At the time, LeWitt was still doing most of the physical work himself. Cooper told me in 2012: “Sol came [to the gallery], and he picked a freestanding awful wall, you could see my storage was behind it—the worst space, and he came and made a drawing on it. It took him two days.” He drew with black pencil the straightest parallel lines he could, in an arrangement that would pre-figure the ideas in many of his works to come — horizontal, vertical, and diagonal.

All of the works at the show were for sale. The asking price for Andre’s sculpture was $1,500; for Flavin’s fluorescent light arrangement, $2,000; for Mangold’s trapezoid $2,500, Ryman’s monochrome painting, $900. The price listed next to LeWitt’s wall drawing was “by the hour.” And even then, any prospective buyer (there were none at the time) couldn’t take the piece off of the wall and carry it home.

Indeed, Cooper’s biggest shock came when the show ended, and the artists came to get the pieces that hadn’t sold. She called LeWitt and asked what she should do with the wall drawing. He told her to paint over it. “I can’t do that,” she replied. So, he went to the studio and did the task himself. It was among his first efforts at the dematerialization of art, and the demonstration that the idea is more important than the execution, a view that would manifest in the system of verification; the only value of a LeWitt wall drawing is in the certificate of ownership itself. The physical piece is worthless.

Or as he would eventually say, among his many wry commentaries, “A wall drawing is permanent until destroyed.”

In all, “Sentences” and its forerunner, “Paragraphs,” words that, according to their author, are not meant to be art itself, have changed basic assumptions that had lasted centuries. At first, as in all revolutions, it was considered fringe. Nowadays, LeWitt’s views don’t seem so extreme.

Thousands of young artists around the world adopted his views and joined his installation crews. They now see LeWitt, who died in 2007, as the artist who has had the most influence, inspiring them to rely more on their heads than their hands. More than 2,000,000 visitors have seen LeWitt’s wall-drawing retrospective (running until 2033) at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art may attest. But as detailed and meticulous as LeWitt’s work and process could be, he was not one to explain the mystery of how or why his art works. When a student at the University of Hartford asked him, “What is art?”, he replied, “It’s a big, fluffy thing.” And, with that, and all he had written down in “Paragraphs” and “Sentences,” he ended his explanation.

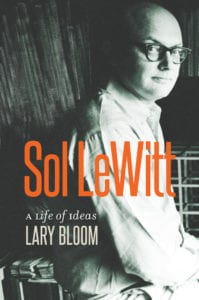

Lary Bloom is the author or coauthor of ten books, including the biography, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, which was published earlier this year by Wesleyan University Press. He lives in New Haven, CT and teaches memoir in Yale’s summer program.

Lary Bloom is the author or coauthor of ten books, including the biography, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, which was published earlier this year by Wesleyan University Press. He lives in New Haven, CT and teaches memoir in Yale’s summer program.

LeWitt saw his role similar to that of a composer or architect whose work is largely done when the score or drawing is finished, leaving the completion to others.

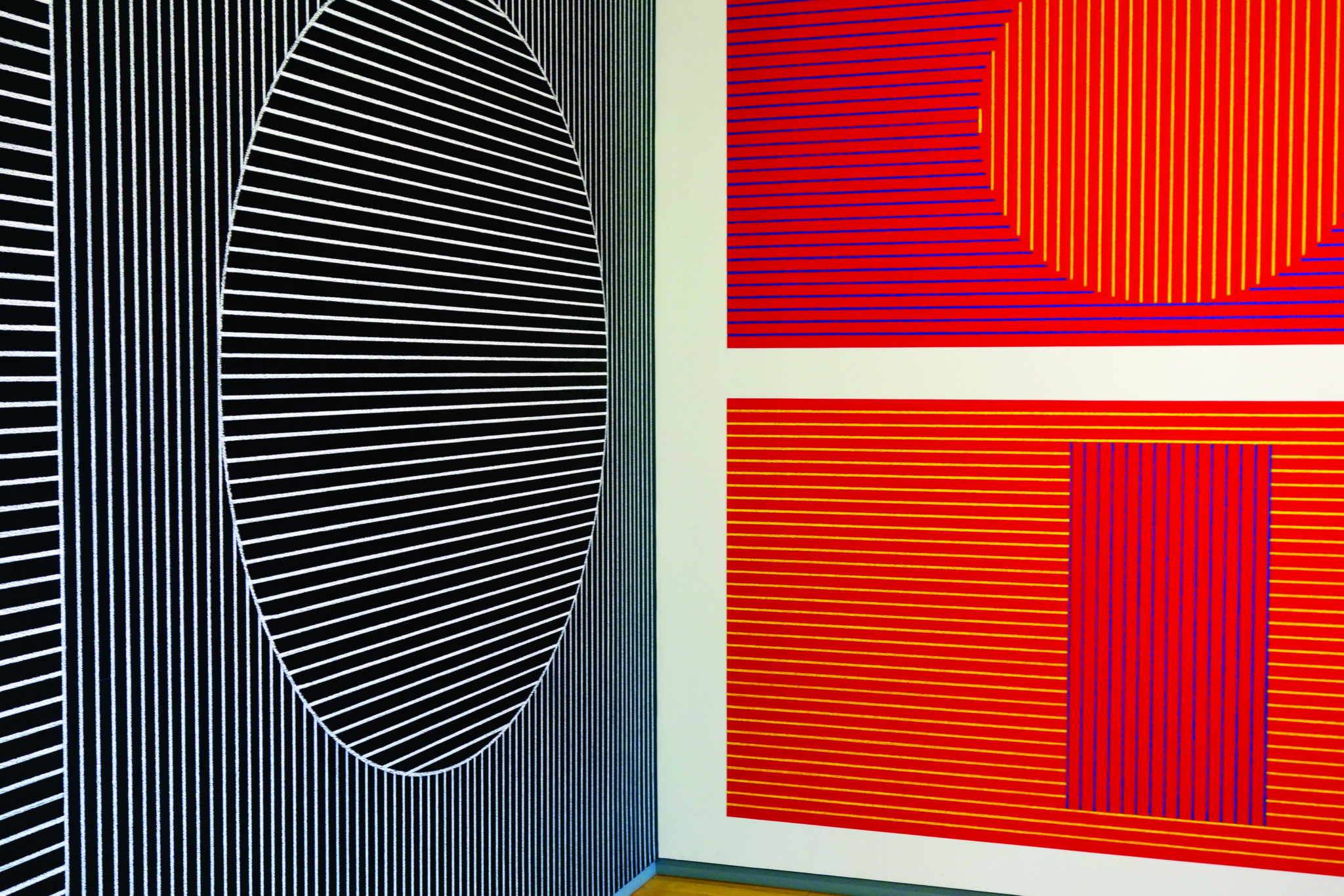

Yet over the last half century, LeWitt’s vast body of work (nearly 1,300 wall drawings and hundreds of “structures” as well as other forms) and his ideas about art have become arguably the most influential as those of any 20th century figure. His name is always attached to two movements, minimalism and conceptualism. Though he often decried such labeling, his writings and practices firmly connected him to the latter category. Moreover, he argued often in public that for the contemporary artist, the brain is much more important than the hand.

His worked showed that, as he was seldom involved with physical installations, leaving that to his crew chiefs and the thousands of young artists he hired over the decades. But it also became central to the installations themselves.

For example, just a few years before he died in 2007, he explained to me that he was asked to do a site-specific installation at an abandoned synagogue in Stommeln, one of the few in the country that hadn’t been destroyed by the Nazis, but which in recent years had been home only to art installations.

His idea was not traditional art at all. That is, no painting, no sculpture, no physical element except for one crude construction: a brick wall. The wall was to be placed inside the entrance, fulling blocking the sanctuary from view. But though visitors to the exhibition would not be able to see what’s inside, they could hear voices. These were the recorded “Lost Voices” of German Jews praying, which I translated from Hebrew into English, along with our friend Reuven Clein. So, the effect was to demonstrate a strong sense of humanity inside, even if it was in the form of ghosts reciting liturgy.

Indeed, the project demonstrated LeWitt’s commitment to the end of his career of what he argued in “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” – that art can be art even if never becomes a physical manifestation and that for artists, “Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically,” that “bad ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution,” and that “It’s hard to bungle a good idea.”

Thus, he amplified what he had written two years earlier, in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” published in Artforum. LeWitt had focused on inception and inspiration rather than what happens afterward. “The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.” The physical creation of the art, he said, is “perfunctory.” In this, he saw his role similar to that of a composer or architect whose work is largely done when the score or drawing is finished, leaving the completion to others.

In “Paragraphs,” his opening salvo challenged conventional thinking of the time, and challenged his peers to seek their own truths rather than the ones defined by critics or market trends: “The editor has written me that he is in favor of avoiding the ‘notion that the artist is a kind of ape that has to be explained by the civilized critic’ This should be good news to both artists and apes.” And he held the view that critics use a secret language meant to impress each other and bamboozle the public. (“Reading art criticism is like chewing glass,” he said.)

LeWitt wrote “Sentences” in 1969 around the time Paula Cooper, a pioneer in SoHo, produced her first show.

LeWitt used “Sentences” to clarify points made in “Paragraphs” and further push the view that artists, far from being fringe societal figures whose talent is expressed by disciplined hands, can do their best work when hands become irrelevant.

LeWitt wrote “Sentences” around the time Paula Cooper, a pioneer in SoHo, produced her first show at her gallery with the assistance of Lucy R. Lippard, who as a writer on contemporary art that had championed the LeWitt circle. Fourteen artists were chosen to participate in the “Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.” Aside from LeWitt and Andre, others selected included Dan Flavin, Robert Ryman, Robert Mangold, Donald Judd and the lone woman, Jo Baer.

At the time, LeWitt was still doing most of the physical work himself. Cooper told me in 2012: “Sol came [to the gallery], and he picked a freestanding awful wall, you could see my storage was behind it—the worst space, and he came and made a drawing on it. It took him two days.” He drew with black pencil the straightest parallel lines he could, in an arrangement that would pre-figure the ideas in many of his works to come — horizontal, vertical, and diagonal.

All of the works at the show were for sale. The asking price for Andre’s sculpture was $1,500; for Flavin’s fluorescent light arrangement, $2,000; for Mangold’s trapezoid $2,500, Ryman’s monochrome painting, $900. The price listed next to LeWitt’s wall drawing was “by the hour.” And even then, any prospective buyer (there were none at the time) couldn’t take the piece off of the wall and carry it home.

Indeed, Cooper’s biggest shock came when the show ended, and the artists came to get the pieces that hadn’t sold. She called LeWitt and asked what she should do with the wall drawing. He told her to paint over it. “I can’t do that,” she replied. So, he went to the studio and did the task himself. It was among his first efforts at the dematerialization of art, and the demonstration that the idea is more important than the execution, a view that would manifest in the system of verification; the only value of a LeWitt wall drawing is in the certificate of ownership itself. The physical piece is worthless.

Or as he would eventually say, among his many wry commentaries, “A wall drawing is permanent until destroyed.”

In all, “Sentences” and its forerunner, “Paragraphs,” words that, according to their author, are not meant to be art itself, have changed basic assumptions that had lasted centuries. At first, as in all revolutions, it was considered fringe. Nowadays, LeWitt’s views don’t seem so extreme.

Thousands of young artists around the world adopted his views and joined his installation crews. They now see LeWitt, who died in 2007, as the artist who has had the most influence, inspiring them to rely more on their heads than their hands. More than 2,000,000 visitors have seen LeWitt’s wall-drawing retrospective (running until 2033) at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art may attest. But as detailed and meticulous as LeWitt’s work and process could be, he was not one to explain the mystery of how or why his art works. When a student at the University of Hartford asked him, “What is art?”, he replied, “It’s a big, fluffy thing.” And, with that, and all he had written down in “Paragraphs” and “Sentences,” he ended his explanation.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column]

Lary Bloom is the author or coauthor of ten books, including the biography, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, which was published earlier this year by Wesleyan University Press. He lives in New Haven, CT and teaches memoir in Yale’s summer program.

Lary Bloom is the author or coauthor of ten books, including the biography, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, which was published earlier this year by Wesleyan University Press. He lives in New Haven, CT and teaches memoir in Yale’s summer program.