I was honored to work with Peter Olchváry to collect and publish these remembrances of his brother Paul, who passed away last February, following a brief illness caused by a pulmonary embolism, symptoms of which went unrecognized. Over the past ten years, I talked with Paul about New Europe Books, the publishing company he founded in 2012, and his perspective on a life in books made a great impression. Our conversations provided a model for many that would follow and to the extent that Vesto has been helpful and effective as a publicity partner to our clients, it has been by an attempt to capture the spirit and enthusiasm that Paul brought to his projects. With thanks to Bob Bettendorf, who introduced me to Paul, and to Jocelyn Giannini at Harper’s Magazine for her support. -JWI

In Paul Olchváry’s exquisite translation, scene after scene, image after image — it is wrenching. . . The details are so precise that any critical distance collapses — nothing’s expected, nothing’s dulled by cliché. It is as immediate a confrontation of the horrors of the camps as I’ve ever encountered. . . The finest examples of Holocaust literature — and “Cold Crematorium” is so fine it transcends its category — aren’t merely bulwarks against obscurity; they do more than allow us to never forget. They offer a glimpse, one that is unyielding and unsoftened by sentimentality, one that is brutally, unbearably close.

–Menachem Kaiser, The New York Times Book Review and author of Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure

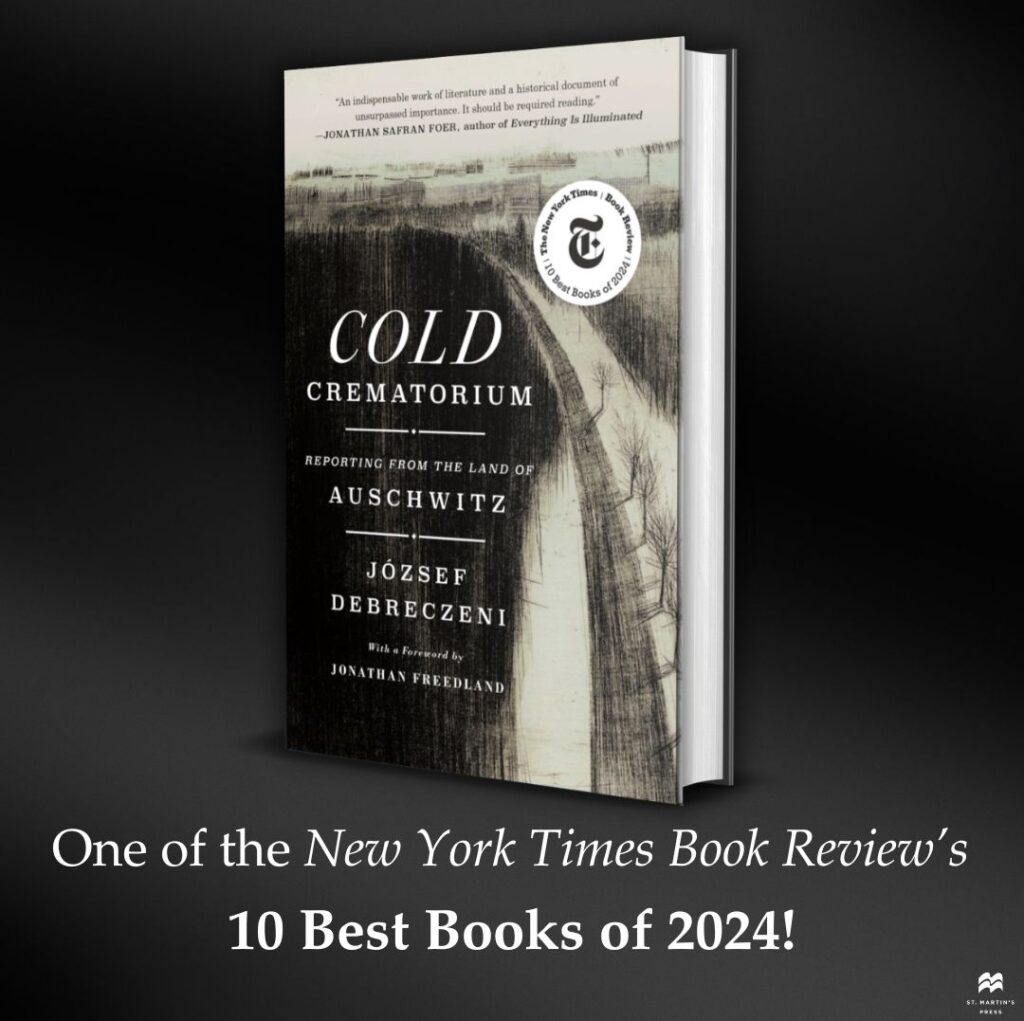

Alex Bruner, nephew of József Debreczeni, author of Cold Crematorium (Paul’s final translation project)

Paul was a passionate, committed, generous, kind, and thoughtful human being. The world of literature, and especially, the world of translation, is poorer for his passing. I have lost a professional colleague and a friend.

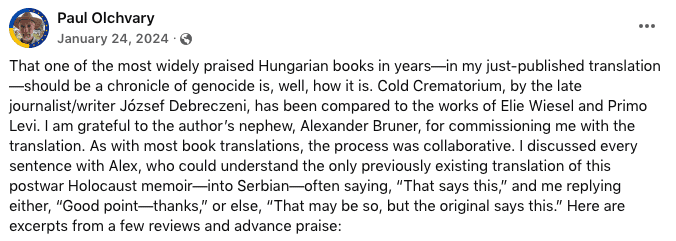

I first met Paul more than three years ago when I selected him to translate my uncle’s Holocaust memoir, Cold Crematorium. Paul was captivated by the work, cared deeply about his craft and the subject matter, and had considerable experience with the specific historical period.

Paul and I worked closely for more than a year, communicating weekly, often daily, agonizing over individual words and phrases. A special challenge was to make the Hungarian text, written by an East European intellectual, feel and sound fresh to today’s Anglophone audience.

A Facebook post from Paul on “Cold Crematorium” and working with Alex Bruner.

The one consolation I have thinking about Paul’s death is that he lived long enough to share in the success of the book and to have his role applauded:

“In Paul Olchváry’s exquisite translation, scene after scene, image after image — it is wrenching. . . The details are so precise that any critical distance collapses — nothing’s expected, nothing’s dulled by cliché. It is as immediate a confrontation of the horrors of the camps as I’ve ever encountered. . . The finest examples of Holocaust literature — and Cold Crematorium is so fine it transcends its category — aren’t merely bulwarks against obscurity; they do more than allow us to never forget. They offer a glimpse, one that is unyielding and unsoftened by sentimentality, one that is brutally, unbearably close.”

–Menachem Kaiser, The New York Times Book Review and author of Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure

“Paul Olchváry, an award-winning and highly accomplished translator of Hungarian literature, has rendered Debreczeni’s prose into a literary diamond — sharp-edged and crystal clear. Like the works of Primo Levi and Vasily Grossman, this is a haunting chronicle of rare, unsettling power.”

–Adam LeBor, The Times of London

“Elegantly translated by Paul Olchváry, Cold Crematorium makes for sobering yet essential reading.“

–Malcolm Forbes, Wall Street Journal

“… in Paul Olchváry’s vivid translation, Debreczeni writes with a cinematic clarity, a determination to make detail triumph over mass dehumanisation.”

–Julian Evans, The Telegraph

Cold Crematorium has been chosen by The New York Times Book Review as one of the Top 10 Books of 2024. It is now available in sixteen languages worldwide. None of this would have been possible without the breakthrough from Paul’s translation from the original Hungarian into English.

Judith Sollosy, Editor, translator, dramaturg, and academic

Few first meetings are memorable, but I will never forget the moment when Paul Olcsvári walked into my office at Corvina Books, Budapest, where I was English-language editor, and Paul said that he would like to become a translator and could I possibly help him. He’d brought with him a translation of an Ádám Bodor short story, I asked him to show it to me. It contained all the givens of an amateur translator, but Paul’s smile and demeanor, and the intelligent twinkle in his eye told me that he’ll be good. Very good. We sat down, and as I critiqued his translation, the color rose in his cheeks, and I thought that if he will now stand the criticism, he’ll be a first-rate translator. The rest, as they say, is history. Both as translator, writer, and later publisher of New Europe Books, which he ran basically single-handedly, Paul demonstrated a keen critical eye for literature. After he left Hungary, we corresponded with some regularity, both about our private lives and matters pertaining to translation, but it was only after some time and quite by chance, that I found out about his publishing venture. Paul was like a brother to me. A good, reliable friend. And a mystery. How can someone so retiring and humble be so dedicated and passionate about his work? He once called me his mentor. I was never his mentor. I was his friend, and I consider myself fortunate to have known him.

What I would like to carve in stone, so that it can never be forgotten, is Paul’s uncanny sense of finding the gems he would then either translate or publish or both. He was brave and bold in his choices and trusted his authors – not for making him rich, but for making the world a better place through words and thoughts. –Eva László-Herbert

Eva László-Herbert, conference interpreter, writer, translator

Paul Olchváry, Pali to some, was a gentle man and a gentleman. He had the manners of the Old World which his parents had to leave. A dear friend who consoled and counseled the best he could. He wrote letters by hand, and even found the time to post them. He had a cat. He had a pipe. He was a teacher. He was a devoted father. He swam in lakes and foraged. He slept under open skies. He loved cooking. He joined the ranks of life guards in his fifties.

As gentle and accommodating he was as a private person, he was uncompromising when it came to publishing. There are many others who will do a better job arguing why his publishing house New Europe Books is unmissable and must go on. What I would like to carve in stone, so that it can never be forgotten, is Paul’s uncanny sense of finding the gems he would then either translate or publish or both. He was brave and bold in his choices and trusted his authors – not for making him rich, but for making the world a better place through words and thoughts. He had an inner compass for matters that matter – just have a look at all the books he published !

It may be going a bit far to call him a masochist, but when it came to his chosen trade – translating – he fought for and with every word with grace and determination, never counting the hours. None of the Hungarian writing he translated was ever easy, charming or mundane. Au contraire ! Through his craft, Pali managed to bring literature written in Hungarian, one of the most dense and passionate languages in the world close to the hearts and minds of readers in English, the language that excels at concision and understatement.

He often spoke of himself as a Bohemian with a pipe and a cat. That might be true – however, it is his integrity, intelligence and intellectual edge he will be remembered for, and his wonderful, brainy wit. A year after his incomprehensible passing, the books he published and translated remain an aching testimony to his 24 carat heart and mind.

An excerpt from “The White King,” prior to the novel’s publication in 2008.

György Dragomán, author of The White King (translated by Paul, published by Hartcourt)

It has been almost a year since the wake of Paul we held here, in Budapest. We sat around the table, a few of us, his remaining friends, drinking red wine, telling stories about him. The time when he didn’t blink an eye when a dozen wild boars ran across the trail in front of him on a hike. The way he would keep talking with his unforgettable half-smile about yet another hopeless love affair. The time, he thought he had eaten lily of the valley instead of wild garlic, and spent the night in his car in the hospital parking lot all night, waiting to see if he had to go to the doctor or if he could somehow get out of paying hundreds of dollars for the examination.

Of course, my best memories of him will always be of us working together on a translation of one of my writings, explaining the rhythm of the sentences and probing the meaning behind the rhythm, he would listen to my explanation, then alter some of the words, reorganize a phrase, we would read each sentence aloud countless times to another, slowly narrowing the gap between the original and the translation, which often seemed hopelessly unbridgeable.

I have always felt that he spent his whole life there, in the space between the “there and there”, halfway between cultures and texts, halfway between writing and translating, halfway between the desk and the reading microphone, halfway between failure and success, halfway between America and Hungary.

We once worked almost continuously round the clock for a week on a text that he would never translate after all, and in the meadows around the residency there were huge statues. We took long walks, talking all the way, first about the text and the work, and then about broader subjects, about fate, about the way writing and translation are a series of decisions, a labyrinth with endless forks and branches.

I still see him hurrying across the meadow in his slightly worn tweed jacket, wanting to get a closer look at the red-rusted metal surface of one of the huge steel rings of a sculpture. That’s how I’ll always remember him, walking across frosty grass, into the harsh bright light of the morning sun, full of curiosity, full of energy. Have a good trip drága Pali!

Ferenc Barnás, author of The Parasite (translated by Paul, published by Seagull)

Paul was a beautiful soul. Those who got to know him more closely could see and sense it. I was lucky enough to have enjoyed his friendship for a number of years. Life is not fair; Paul knew that. That might have been one of the reasons why he became a translator. He was an eager promoter of Hungarian literature. I am one of the Hungarian writers whose novels (the first two) were made accessible to Anglo-Saxon readers thanks to his great translations. I will be indebted to him for this forever.

Chris Mele, The New York Times (Paul and Chris both worked as reporters at the Adirondack Daily Enterprise in Saranac Lake, NY in the late 1980s)

Paul was a gentle soul whose natural curiosity and goodwill were contagious. I could never recall a time that Paul was cross or unhappy. My memories are clearly of him smiling and eyes sparkling, sometimes with mischief! His passing is such a loss. May his memory be a blessing.

David Bukszpan, author of Crosswordese & freelance publicist (David was the publicist for Duncan Robertson’s Visegrad)

The one word that seemed to inevitably come up when anyone mentioned Paul was “mensch.” I mean, he was a menschy as they come. He was so essentially goodhearted, so decent, modest, and kind, that when I was first got to know him it seemed hard to believe. But as I grew to know him more, I saw he really was a marvel of a generosity of spirit, readily giving of himself for projects and causes he believed in. These are dark days, days we could use more men like Paul. Let him be a model for us, his memory inspiring us to fight with righteous indignation ourselves, and to have faith that there is plenty of goodness out there—beautiful mensches quietly working to make the world a better place.

John K. Cox, Professor of East European History at North Dakota State University

Paul was an inspiration, and I will never forget him. We met in Bloomington and worked together on various projects later. His press is a wonderful legacy, but he was also a devoted father, a generous and quirky and unfailingly gracious colleague, and, truly, the finest translator I have ever known, from Hungarian or any other language. He’s one of the people about whom we pause and say, “My life is better because he’s in it.” I will never forget him.

Gazmend Kapllani, author of A Short Border Handbook (New Europe Books in the US; Granta Books in the UK)

Paul was a uniquely talented and kind person, an avid reader, a brilliant translator, and a courageous publisher, with an amazing sense of humor and a big heart. Paul had lived in Europe, especially in Hungary where his roots were, and we often spoke about Europe together – sharing that rare and entertaining intellectual and spiritual chemistry that only Eastern Europeans meeting in America know about. I’ll remember how we could pass with amazing easiness from intellectual discussions about literature, to discussions about politics in Europe and America, to everyday life details. I was a new migrant to America when I first met Paul, after he decided to publish my first novel here in the US with his New Europe Books based in Massachusetts. Now the novel, thanks also to that edition, is taught in American colleges and universities. Thanks to Paul, I met other talented writers and translators. I deeply miss him, our conversations, his humor, his unparalleled kindness, especially in these crazy and unkind times. For me and for others who knew him he will never be forgotten.

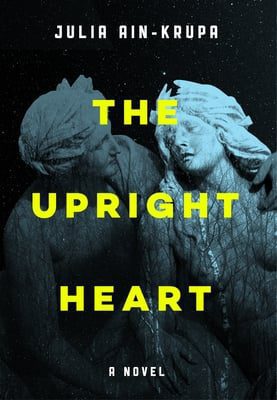

Julia Ain-Krupa, author of The Upright Heart (New Europe Books)

Paul Olchvary was a kind and gentle soul who cared deeply about literature and human kindness in equal measure. He leaves a vacuum in the world of letters. He is deeply missed.

Mikhail Iossel, author of Notes from Cyberground (New Europe Books)

I miss him. He was a warm, smart, beautiful, passionate and compassionate man. HIs early death is an affront to the naive notion of life’s fairness. Life is unfair. He’s left behind books and memories. Meaningful books and long-lasting memories. He left behind his son, his relatives, his friends, and the readers of his books. He is missed and will continue to be missed. I miss him.

One night while staying at my home, he did some translating work and as I watched I was astonished just how effortlessly he rendered Hungarian poetry into elegant English. I am functional in a few languages but I cannot move between any of them (including my native language) with the same eloquence and grace that Paul could between English and Hungarian. –Tomek Jankowski

Tomek Jankowski, author of Eastern Europe! (New Europe Books)

I had started studies in Pécs, Hungary in the late 1980s when my department asked me to greet a newly-arrived batch of American exchange students. I marched up to their dormitory and was chatting with one when, in the natural course of discussion, we asked each other where we were respectively from. When she heard me mention Buffalo, NY, she suddenly bolted down the hall and returned with a tall, gangly, bespeckled guy with a shock of hair and dark eyes, but an oddly disarming smile. That is when I met Paul, and we’ve been friends ever since. We even ended up as roommates a couple times. Time spent with Paul was filled with adventure, lots of laughter, serious conversation, good food and wine, and sometimes absurd discussions, but always – kindness and collegiality.

Maybe a year or so later, I happened into our department one morning only to notice Paul in the bathroom intently staring into the mirror. Completely on a whim, he had spent the night sleeping outdoors in the Mecsek Hills, covered only in leaves. When I ran into him, he was busily picking out the ticks before his classes. This was a typical encounter with Paul.

Afternoons in the Rudas fürdő/Ottoman thermal spring bathhouse, vineyard hikes in the Mecsek Hills, or chatting with his parents in Amherst: so many memories. Paul occasionally creeped me out with his amazing ability to transform his face into a decrepit, old man. That was a party favorite.

He was an amiable person who put people at ease, so much so that many often underestimated his intellect. He was a serious scholar who dabbled in multiple fields and his capabilities spanned translating, copyediting, journalism, professional organization and formatting, and what I’ll call messaging – knowing how to deploy precisely the right words to make a point. One night while staying at my home, he did some translating work and as I watched I was astonished just how effortlessly he rendered Hungarian poetry into elegant English. I am functional in a few languages but I cannot move between any of them (including my native language) with the same eloquence and grace that Paul could between English and Hungarian. He brought words to life in ways that captured their full cultural context, but which looked natural and effortless on the page. In contrast, any translation I attempt results in armies of clumsy footnotes. Paul truly was an artist.

To that point, later in his life he focused more on these skill sets (they paid the bills), unfortunately at the expense of his own writing. We are all the poorer for his having never succeeded in fulfilling his own writing dreams. When we first met, we were both aspiring authors. Somewhere in his head was the next Great American Novel. I wish he had taken more time to fulfill that dream.

Another of my friends once described Paul like a Kálmán Mikszáth character, like a nobleman deprived of his castle but still living a carefree life unbound by any mundane daily cares or concerns. Paul was a genuinely curious guy which (as I mentioned) led to adventures. It was a genuine revelation (and a joy) to get a glimpse of the world through Paul’s eyes. This meant that he also attracted a large group of often very strange friends, so that moving in Paul’s social circles was to meet usually very odd or socially awkward people – but people who were very intelligent and engaged with the world intensely in unique ways. Admittedly, coming from a small town myself, being included in Paul’s social milieu helped break down some of my own narrow preconceptions and social attitudes, for which I am grateful.

He loved his son deeply, and he took his role as a father very seriously. I cannot recall a conversation we had since his son’s birth in which Paul did not at some point bring him up, usually sharing anecdotes of hiking or something else they did together.

Finally, I’ll mention my own debt to Paul for his willingness to take on my manuscript as a publisher. As I mentioned, we once both had dreams of becoming authors. Paul sacrificed some of his own dreams to help mine come true.

He was a good friend, but more than that, he was an amazing person to have in my life, someone who challenged and nurtured a healthy sense of inquisitiveness, skepticism, wonder, and empathy in all who knew him.

As is all too often the case with good people, I mistakenly believed we would have more time together – so much more time, so many more laughs and discussions. A year later, I am still reeling from his sudden passing. I can only feel for his family. Our last conversation was very casual, a normal chat – not the epic goodbye it turned out to be. Still, I am grateful we had that opportunity, and now I find myself among his friends who are left to reflect on how lucky we were to have had someone like Paul in our lives.

Alex Olchowski, Writer, Artist, Farmer

My friend Paul, also known as Pali, and by his “animal name” Heron Paul, communed deeply with spirits born from a myriad of sources. Forests and lakes. Well-worn books. Pen pressed to paper carving elegant words to a lover or a friend. To his mother or his son. The few fish he caught and the many fish he didn’t catch. A tent pitched beside a national forest dirt access road. Anything Hungarian, most especially the paprika Chicken dish he inspired me to master myself over the years.

Paul drank from the purest waters of life. He was equally satiated by the cobbled stone canals of an ancient European city as he was by the quick fresh creeks tumbling down the nooks and crannies of Mount Greylock, being anywhere along his beloved Hoosic River, or circumnavigating Windsor Lake by doing the crawl for an hour and a half straight no matter the temperature of water or air. Canoe paddles breaking a calm Adirondack pond at dawn. Collecting firewood in the dusk. Engaging intimately with skipping stones and wild mustard greens. Stripping invasive Japanese knot weed of its rhubarb skin. And, most of all, Paul kept himself connected to this Earth by connecting with his fellow human beings in the most authentic, uninhibited ways possible.

Paul Eugene Steven Olchvary opened his heart to the world, and at times he suffered for his sensitive selflessness. But then there were the many times he took the flights of magic and hope, brave in ways many people never even noticed, a courageous practitioner of the art of living. Paul was an Artist of life itself. I’ve said this to many people over my thirteen years of being his very close friend.

Paul touched people almost immediately after meeting them. He was imbued with a visceral passion for the essence of any given moment. When he conversed with you, you received the endorphin boost of a rare encounter with someone who truly wanted to know you on a deep level. What got your blood flowing. What you loved in this life. Being an artist of any kind is not an easy path. Paul developed and honed such beautiful ways of coping with the challenges of what was often a precarious and chaotic existence for him. His wooden tobacco pipe was a sacred object, simultaneously connecting him with the ground and the cosmos. His pipe was a trusted friend. It was a tool of power and comfort for him rather than any crutch. Paul survived this often cold and empty world by reaching out, calling up his mom or brother or a close friend at any time of day. And it often turned out that whomever he’d dialed up actually needed to talk even more than Paul did. So, in this way, he helped the rest of us survive, too. He battled his existential bouts of loneliness and worry by handwriting someone a letter. Taking a long spontaneous walk in the woods. Making a fire in his backyard. Staying up late watching an old black & white classic movie, which happened to be an activity he cherished doing with his beloved son. And Paul worked Hard! Sometimes seven days a week, well into the night, on his translation projects and the many endless tasks of an independent book publisher. Without a commute, office, or coworkers, his work-life was about as isolated as one can be. But oh did he love it.

A favorite memory I possess of my time with Paul was when we backpacked into Hour Pond (spelled like an hour of time) 6 miles deep in the North Central Adirondack wilderness, and camped there for 2 nights. That first afternoon we both wrote by hand in our notebooks while sprawled on the soft, pine needled forest floor. Paul on a translation text and me on a new novel manuscript. It was moments like these at Hour Pond, bonding further during the earlier years of our friendship in a truly wild place, that encapsulated the two worlds we both cherished – literary arts and nature. How both of these could compliment one another was something we each felt deeply and shared together from the day we first met, sitting next to each other writing by hand at Tunnel City coffee shop in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Paul touched so many. And for this reason he will live on in all of our hearts. We love you Pali.

Pali was a devoted father, and I could hear the love for his son every time he spoke of him. –Jeff Pennington

Jeff Pennington, Executive Director of the Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies University of California, Berkeley

I first met Paul Olchvary—“Pali”, as he told me to call him—in September 1988 during our first semester of graduate school at Indiana University Bloomington. Pali was just starting an MA in creative writing, I was just starting an MA in East European studies; we were both in 3rd-year Hungarian language class. As a heritage speaker of Hungarian, Pali excelled in the class, taking it more to give himself a deeper knowledge of the complexities of the language. His leadership, linguistic facility, and interest in Hungary stood out, so much so that during our second year in graduate school, he became president of the Hungarian Cultural Association at IU. One of the duties of the president was to serve as emcee at the HCA’s two major events during the year: one around October 23 to commemorate the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the other around March 15 to commemorate the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. Though he never seemed to be completely comfortable speaking in front of a crowd, he handled the emcee duties in both English and Hungarian with aplomb. As secretary of the HCA, I was able to observe firsthand Pali’s interaction with the group’s different constituencies—students, faculty, community members—and that’s when I began to recognize Pali’s most positive character traits, which stayed with him throughout his life: graciousness, kindness, and generosity.

Pali finished his writing program in May 1990 and subsequently moved to Hungary, at first to teach English. I moved next door to Romania for a year to pursue research. Limited finances and distance, aggravated by slow trains and hours-long waits at the border, meant we didn’t get a chance to visit each other during this time. However, our paths began to cross again in fall 1992, when Pali began working at the U.S. Embassy in Budapest on an internship known as the “Fascell Fellowship,” and I started a year of research in Debrecen, Hungary. The embassy provided Pali a rather large apartment on the “rakpart” on the Pest side of the Danube. Probably constructed in the interwar period for bourgeois families, the apartment had a small bedroom next to the kitchen (ostensibly for the housekeeper or cook), and Pali generously offered me a place to stay in that bedroom when I’d come to Budapest to work in the archives and national library. I owe him greatly for helping me to be able complete my research for my MA thesis and a subsequent article.

Following the embassy internship, Pali stayed in Budapest and resumed his career as a translator. I left Hungary in summer 1993 and eventually moved to Bucharest, Romania for a job. Now having a more steady income, I could afford to travel to Budapest on occasion to escape the sometimes-dreary whiles of Bucharest, and Pali was always there to meet me. If he couldn’t offer me a place to stay (he was living with someone at the time), we would at least find time for a nice dinner and walk through the city, so we could tell each other about our latest exploits. Finally, in about 1995-1996, I was able to reciprocate Pali’s hospitality when he began to come to Bucharest to visit. He would sometimes stay at my place, got to meet my circle of friends, and got to explore Bucharest of the mid-1990s (which wasn’t on many people’s itineraries at that time).

Pali and I lost contact for a few years when, in summer 1997, the vagaries of life took me to Japan to teach English. We eventually reconnected and renewed our friendship in 2000, when we both moved back to the U.S. for work—he at Princeton University Press, I at IU Bloomington. At some time during the winter of 2000-2001, I visited him in Princeton. Now on the same side of the pond, we had each other’s emails and phone numbers, so staying in touch became a lot easier, even if we weren’t able to meet in person as frequently as we would’ve liked. Distance meant meeting in person wasn’t always a possibility (Pali eventually moved to Williamstown, Massachusetts, I to the San Francisco Bay Area), so there were a lot of long emails and phone calls.

But I recall two more times when Pali and I met since then. One occurred on a snowy Sunday in Madison, Connecticut, in January 2009; his son had been born just a few months earlier. For lunch, Pali made one of his famous paprikás dishes, this time harcsapaprikás (catfish paprikash). Pali liked to cook Hungarian food. I remember in the 1990s he had two go-to dishes. If he were in a hurry, he’d cook up lecsó, a dish of sautéed onions and yellow and/or red peppers, with which you’d usually serve a meat, often sausage. If he had more time, he’d cook a paprikás of some sort. His was home-style cooking.

Of course, my last get-together with Pali sticks out most vividly in my mind, especially because it happened less than two years ago and just a couple of months before his stupid and untimely passing. In August 2023, my partner Jonathan and I were on a driving tour of upstate New York and New England. Jonathan had never met Pali, although I had told Pali all about Jonathan, and Pali always asked how he was doing every time we spoke on the phone, so we arranged to stay a few nights in Williamstown. On our first night there, we invited Pali to dinner at a local restaurant. Pali reciprocated by inviting us to dinner the following evening at his place, also giving us a chance to meet his son and Pali’s partner. I hadn’t seen his son since he was just a couple of months old, but Pali had kept me up to speed with him over the years. Pali was a devoted father, and I could hear the love for his son every time he spoke of him. This was also the first time to meet his girlfriend, about whom Pali had told me so much in phone conversations over the past few years. It comforted me to know that Pali had found someone in his partner who was making him happy and giving him a new perspective on life. In his usual style as host, Pali cooked paprikás, this time csirkepaprikás (chicken paprikash). It was delicious.

Pali, Jeff bácsi misses you. We all miss you!

Paul in the late 90s, living in Hungary.