By Jeremy Wang-Iverson

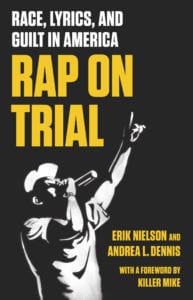

Last fall, The New Press published Erik Nielson and Andrea L. Dennis’s Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics and Guilt in America. The book examines a very specific but insidious action on the part of prosecutors over the past three decades: citing rap and hip-hop lyrics and video in court cases to persuade juries to make convictions. Nielson, associate professor of liberal arts at the University of Richmond, and Dennis, professor at University of Georgia School of Law, offer fascinating legal analysis and cultural criticism in this important contribution to the publisher’s unrivaled list of criminal justice titles. Nielson and Dennis discussed their work, some examples of Rap on Trial in action, how they came to collaborate on this project.

When did each of you first become aware of the extent to which rap lyrics were being used in America’s courtrooms?

Andrea first encountered this tactic in the early 2000s when she was a criminal defense attorney. About five years later the issue landed back on her radar when she was researching connections between hip hop and the law. At that time, she realized the practice was more than just occasional and isolated, leading her in 2007 to publish her law review article entitled Poetic (In)Justice? At the conclusion of the article, she opined that technological advances, such as social media, would facilitate the spread of the practice. She was right. By 2012, it was clear that state and federal law enforcement and prosecutors nationwide were using rap evidence in every phase of the criminal justice process.

Erik has served as an expert witness or consultant in roughly 50 cases involving rap lyrics as evidence. Ironically, his work in U.S. courts began thanks to the work of Eithne Quinn, a British scholar at the University of Manchester, who had begun working on cases in which grime (similar to rap) was being used as evidence in the UK. Suspecting that if the practice was occurring in the UK, it was likely happening in the U.S., Erik began looking. It quickly became clear that it was widespread, but he didn’t appreciate the full scope of the problem until he and Andrea teamed up to begin looking in earnest.

At present they have identified hundreds of cases and suspect that thousands remain hidden from public view.

“Rap music is the only fictional musical genre used this way because its primary producers are young Black men, who the criminal justice system happens to target.”

Why are rap lyrics so much more likely to be introduced as evidence than lyrics from other musical genres?

Rap music is the only fictional musical genre used this way because its primary producers are young Black men, who the criminal justice system happens to target. Police and prosecutors highly value statements and conduct by a defendant that can be argued as self-incriminating. Rap lyrics often fit this mold because they are usually written in the first person, and oftentimes focus on criminal themes and use violent imagery. Lyrics that reinforce common narratives and stereotypes that Black men are dangerous criminals are powerful influences on judges and jurors.

Class also plays a factor. Most defendants in these cases are overwhelmingly black or Latino, most of them amateur rappers without the name recognition or financial resources that insulate more prominent artists.

Studies have shown that people perceive the same song lyrics as more damning of the writer when they are told they come from a rap song than a country song—is that because rap is a predominantly African-American genre?

Studies have shown that people perceive the same song lyrics as more damning of the writer when they are told they come from a rap song than a country song—is that because rap is a predominantly African-American genre?

Yes. The lyrics are also perceived as more threatening and in need of regulation. They are also more likely to be read literally. This is thanks to other stereotypes, namely that young Black and brown men are incapable of producing sophisticated art, so their lyrics must be literal. There’s no acknowledgement of their ability to master complex poetics.

Why do prosecutors and juries have so much trouble distinguishing the real and fictional identities of rappers?

Sometimes they’re simply uninformed, or misinformed, about the conventions of the genre, and don’t understand that it is a fictional art form even when based on reality. But in other instances, prosecutors and juries are actually unwilling or unable to accept the idea that an artist—particularly an amateur—is appealing to an audience that craves hyperbole, exaggeration, and realism, and deploying sophisticated artistic strategies to do so. For example, a juror may struggle to reconcile use of the first-person narrative in lyrics with fake personas and false claims of authenticity.

And we can go a step further. In some cases it’s clear that prosecutors and police “gang experts” are knowingly misrepresenting rap music to judges and jurors in order to secure convictions.

What are some of the most common misperceptions about hip-hop that you have encountered?

That it’s all violent and hypersexual. There’s often no understanding that like any major art form, there is variety and rap artists explore a wide range of themes and ideas in their music.

Another is that it’s not music. Another is that it’s definitely not poetry.

For our purposes, the most important misperception—aside from the idea that rap lyrics are autobiographical—is that rap perpetuates violence. The history of rap music, as well as hip hop culture generally, tells a very different story.

You write that famous rappers have found it easier to defend their lyrics in court. Why is that? And should it matter to the court whether lyrics were written by a professional or amateur rapper?

One explanation is that money buys justice. Well-resourced defendants have always fared better in the criminal justice system. Another explanation is that people generally believe that a famous or commercially successful artist is a true creative—not just spinning real life tales in musical form. But up-and-coming amateur artists are perceived as writing lyrics that are simplistic, rough, and crude.

What are some of the ways prosecutors use rap lyrics in criminal trials?

- As evidence of a true threat directed at someone else. (That’s when the lyrics themselves are the crime).

- As confessions.

- As evidence of a person’s motive or identity with respect to a crime.

- In many, many cases, to establish gang affiliation.

And in a new spin, we’re beginning to see prosecutors who allege that, even though a defendant did not personally commit a criminal act (e.g., homicide, assault, drug distribution), the defendant should be convicted of conspiracy because he wrote lyrics that described, encouraged, or facilitated a gang’s criminal acts.

“We hope this book serves as a wake-up call to criminal defense attorneys who are not aware of the issue or how to battle back.”

Have judges set any limits to how rap lyrics can be used at trial?

Overwhelmingly, judges have set very few limits. They’ve uniformly rejected constitutional arguments that would preclude using these lyrics as evidence and rarely bar their use during trails. Defendants generally prevail only in extreme cases such as when prosecutors violate court rulings or make highly inflammatory arguments based on the rap lyrics being used as evidence.

What can defense lawyers do to fight back against the use of rap lyrics to prosecute their clients?

We hope this book serves as a wake-up call to criminal defense attorneys who are not aware of the issue or how to battle back. Luckily, there are many tools available to challenge the practice in criminal court. One of the easiest approaches is for a defense attorney to use an expert to counter the often- demonstrably-false narratives of police and prosecutors, who generally know next to nothing about rap music.

But alongside litigation, attorneys must work to draw public attention to the practice and the injustices it causes. We believe that they can play a significant role in educating judges and citizens, i.e., potential jurors, of the extent and perils of the practice.

Are there any potential legislative solutions to the problems you outline in this book?

We call on legislatures nationwide to rely on the First Amendment to enact rules shielding rap music, a form of expressive speech, from being used against artists to impose criminal penalties on them. We call these protections rap shield rules.

Buy the book from Bookshop.org.

Erik Nielson is an associate professor of liberal arts at the University of Richmond, where he teaches courses on African American literature and hip-hop culture. He lives in Richmond, Virginia and Brooklyn, New York. Follow Erik on Twitter: @ErikNielson

Andrea L. Dennis holds the John Byrd Martin Chair of Law at the University of Georgia School of Law and was formerly an assistant federal public defender. She lives in Athens, Georgia. Follow Andrea on Twitter: @ProfALDennis