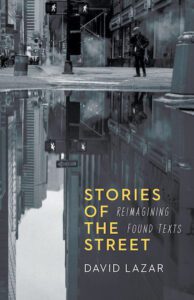

David Lazar’s new collection of essays, Stories of the Street: Reimagining Found Texts, is series of imaginative meditations—through prose poems, short-short essays, microfictions, and prose pieces without precise genre distinction—of what it means to encounter lost or discarded texts. It was published this month by University of Nebraska Press.

This interview first appeared on Derek Krissoff’s Book Work.

How did the idea for this collection come about and how long did you work on it?

How did the idea for this collection come about and how long did you work on it?

Walking has always been one of my greatest pleasures, and I love to walk in cities. I’m from Brooklyn and we walked and walked. Later, but way before I learned about Montaigne’s perambulating percolations, I discovered that I did some of my most fertile thinking when walking alone. So: I believe it began during a walk in Chicago and finding one interesting text on the sidewalk. I don’t remember which one it was, but it occurred to me that among the litter were messages, lost and discarded. And after finding another, and then another, I realized that there were written and printed texts everywhere if you looked. So, gaze downward, I started collecting them. I photographed each piece in place, so I must have had the idea for a sequence, a book, early on. I’d say I collected the evidence in the book and wrote the accompanying pieces over a ten or twelve year span.

What was your process for uncovering the stories within each item or text?

Since the actual story of each fragment (what to call them? Texts, messages?) was unknowable, I thought what I could do was imagine the writer and circumstances, and/or extend the texts to someplace strange and interesting. It’s really a book of persona prose poems in many ways, since for each find I had to imagine the writer and why they had written what they did. In some cases, why the text was discarded. So I started with close reading, and proceeded to doing what we do: imagine a scenario and what it might mean.

Did you find yourself drawn to a specific type of item? Did any sort of pattern emerge?

There are so many different types of texts that I’m not sure I could identify a pattern. But I can say that I was especially interested in handwritten notes and strange or elusive pieces of writing. I loved finding a card that just said “4:30 a.m.” Questions bloomed! Why so early, and where? Were you meeting someone, or is it just a reminder of when the carriage is going to turn into a pumpkin?

You utilize various writing styles in this book. Did each item call for a certain form or did you try different methods for the same object?

I think really each piece has a different form. There are some basic similarities—all but one are in prose, some elements of microfiction, prose poetry, short short essay, dialogue. But, other than the villanelle, I didn’t begin any of the pieces with a foreordained form. And some of them evolve into forms different from their beginnings.

These lost items can be seen as anything from humorous to forlorn but certainly open to interpretation. How did you find the narrative voice for each story?

Each of the found texts came to me with mixture of the known and the unknown. The known is the text, obviously, and the unknown includes (mostly) the writer, their circumstances, frequently their gender, and most importantly their emotional and psychological relationship to what they had written or carried. My task then was to fill that vessel with something interesting, perhaps (though not necessarily) plausible. Sometimes the found text is a spur, an occasion, a stimulus, and my work connects to the text in a slanted way. In other pieces, the text itself is crucial to what I’ve written, which is a kind of imaginative gloss.

Did you find yourself having an initial reaction to the items but upon revisiting them a new feeling or story unfolded?

Great question: yes. Some of my initial reactions were pretty basic and conventional: oh, this child’s homework, how sweet. Or: isn’t this poor young guy in a depressive hole. But to move into their voices was to find, and invent, a stranger and more tangled narrative: to imagine a subtext to the text that was possible, even if not legible.

Seeing them became very important to me, and as frequently happens, the more I looked, the more I found. Communication through accident or loss, through carelessness or abandonment is still communication, but it requires a finder, a reader, salvage. It became important to me, even with the texts I ended up not using or even writing about, to be the reader for lost messages.

The book documents the detritus of urban human life. Can you talk a bit about why it was important to you to give a story to these lost items and texts?

The world is full of all kinds of messages. As Alexander Smith wrote in the 19th century, “The world is everywhere whispering essays, and one need only be the world’s amanuensis.” It’s a lovely line, and a good start: first is the recovery, taking the lost messages and actually seeing them. Seeing them became very important to me, and as frequently happens, the more I looked, the more I found. Communication through accident or loss, through carelessness or abandonment is still communication, but it requires a finder, a reader, salvage. It became important to me, even with the texts I ended up not using or even writing about, to be the reader for lost messages.

Did you find yourself exploring the idea of a lost versus discarded item? How did that show up in your work?

They’re both interesting and important to me, and they have different emotional valences. In both cases there is the possibility of the melancholic or forlorn consequence—the anger or sadness of tossing a message down (sometimes one the discarder hasn’t written, which makes me the second reader), and the orphaning of messages which seem to have eluded their owners. The loser of messages doesn’t have a sense of their possible telephone game-like life, whereas the discarder (who could always have destroyed the message) is in effect passing it one.

How much material did you leave out of the final collection?

Quite a bit—probably the same number as in the book. And I’ve continued collecting material. Living close to NYC now, and spending a lot of time in the city, I have days that seem like textual feasts in the amount of material I find in the streets. I’d love to do a sequel, perhaps with a different organization or take on what I’ve found.

How has your career as a professor influenced your writing?

A lot! In the classroom I’ve frequently done sections on walking literature, and walking films, too. The walking essay is a vibrant sub-genre (Dickens! Woolf! Hazlitt and Lamb!) and there’s a walking component to many essays. I used to send my students out on walks, sometimes with recordings, sometimes not. I’ve been able to teach what most interests me, and so teaching has included material on walking, because walking is one of my life’s continuing joys. What I think about what I think has always been influenced by the rich dialogue of the classroom.

Were you inspired by art movements such as found object and trash art?

Yes to both, and outsider art, as well. DuChamps, Beuys, Tracey Emin, Marina DeBris, etc . . . I’ve always thought that to some extent all art is found art, but artists working directly with found objects have always interested me since they’re saying, “Look what this can become; look at how context transforms,” which is generally true of art making.

Which writers would you count among your influences?

Hazlitt, Lamb, M.F.K Fisher, Laurence Sterne, Henry James, Georges Perec, Benchley . . . . There are many writers I love whom I don’t think my own work was recognizably influenced by, like Woolf, Baldwin, or Montaigne. But I’m sure there are subtle traces, in the ways I think certainly.

What books are on your bedside table now?

I just finished reading Kate O’Brien’s Country Girl novels, and Annie Ernaux’s new book The Use of Photography just came in the mail. Also, Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, which I’ve never read, but want to circle back to after reading Kate Summerscale’s wonderful The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher.

Can you say what your next project will be?

Yes, the next book is mostly a collection of collaborative essays, epistles or calls and responses with a few different writers, who happen to be women. It’s called Double Indemnities, and Nebraska will publish it in a couple of years. The collaborations are ongoing, and then I have to do a lot of editing.

David Lazar is the author or editor of numerous books, including Celeste Holm Syndrome, I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays and Aphorisms, Truth in Nonfiction, Occasional Desire: Essays, and The Body of Brooklyn.