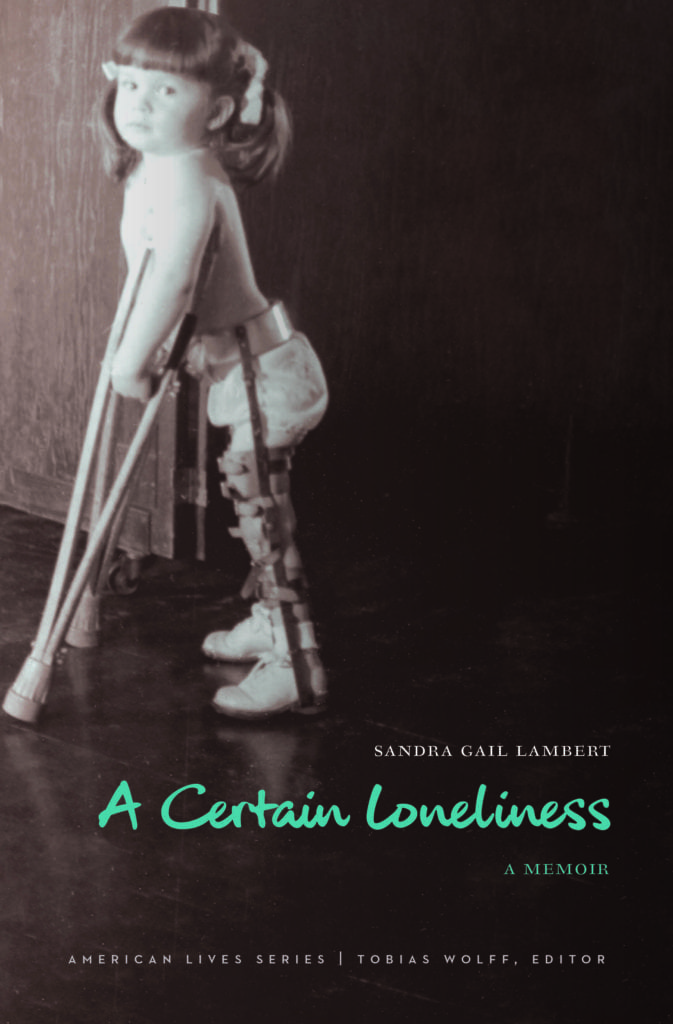

Sandra Gail Lambert’s memoir A Certain Loneliness will be published on September 1 by University of Nebraska Press. A reviewer for Kirkus said “Lambert makes beautifully palpable the exquisite liberation she finally experienced when exchanging her braces and crutches for a manual (and then automatic) wheelchair. Each of these recollections is unhurriedly told and expressed with true introspection; the author knows herself well and shares thoughts, feelings, and impressions with grace and acute self-awareness.” Lambert is the recipient of a 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship and the author of a novel The River’s Memory. She lives with her wife in Gainesville, Florida.

When did you start writing A Certain Loneliness?

Placed throughout the memoir are flashes of memory that span forty years, each one connected to the old Sears Building in Atlanta. The first of those was written in the 1980’s at a lesbian writers conference in South Georgia, but it wasn’t until 2005, after writing a first, unpublished novel, that I returned to personal essays. It was over the next decade that I wrote the collection of memoir, essays, and reflective moments that became A Certain Loneliness.

What was it like writing memoir after having published your novel, The River’s Memory?

Before, during, and after the writing and ultimate publication of The River’s Memory, I wrote personal essays. The immersion required for long-term projects such as a novel can be isolating and as with all writing, there are stops and starts and times of procrastination and the intermittent yet certain belief that your novel isn’t going anywhere or worth anything. I’ve found that working on essays helps. It’s satisfying to start and finish an essay during the extended timeline of novel writing. And if the essay is then published, there is an interaction with readers and the literary community that helps sustain me during what would otherwise be a long absence.

Did you do research or interviews to write about your life? What was your process like?

I have a terrible memory, especially of my childhood, which is not something that engenders confidence in someone trying to write a memoir. And now that I’ve admitted it out loud, I wouldn’t blame any potential readers for also being wary of my truthfulness. But here are some of the ways I work around these gaps of memory.

One of the essays in the memoir, “May or May Not” is a direct example of writing through a childhood scene where specific memories—the pattern of tile on the bathroom floor, the fascination with the long legs of my mother’s friends, the smell of warm beer—are fleshed out with what I know must have been true from geography, climate facts, and family stories as well as my speculations and questions on what might have been true.

Other sections of the memoir are more narrative—for instance, the tales of kayaking in the Okefenokee Swamp and in the Everglades. To offset my imperfect memory, I’ve learned to keep a yellow pad full of notes for each of my trips and excursions. They have dates, tide levels, reports on how my body is fairing, the weather, a list of butterflies and birds, my dreams, what I’m reading, a range of personal anxieties, and whatever I’ve learned about the ancient geologic forces surrounding me. These notes, usually many years later, become the generative force of essays.

You also write about movement and landscape in lush detail. What draws you to these elements?

A result of the increasing fatigue, pain, and weakness of post-polio syndrome was that I had to figure out new ways managing my life including how I moved my body through the world. One change was that I started using a wheelchair. Others were that I quit my job, qualified for Social Security Disability Insurance, and moved to Florida. So now my access to places and money was restricted, but I also had less pain and more time. And I had left a city and moved to a part of the world with crystalline springs that burst up from layers of silent, underground lakes and salt marshes that smelled rich with both new and decaying life. The freedoms and limits using a wheelchair offered became intertwined with the physical and emotional joy of exploring the natural world. I’d wedge my kayak between two cypress knees in a still swamp and lean back to rest my arms for a while. I had all the time I needed. And I’d return from these “middle of nowhere” places and write about the complexities of chance, adaptation, and desire that made my new life possible. So the ways I engaged with the natural world became core to my memoir—to both the content of it and to its creation.

How did you come up with the title?

There is all sorts of advice, often conflicting, about titles. It should be attention grabbing or poetic or memorable or have layers of meaning or be descriptive of the contents or easy to say. Looking back at my many drafts I find a bunch of place-holder titles such as “Rolling in the Mud,” “Skin Loneliness,” “The Poster Child,” “Swimming,” and “Well-Nourished White Child.” For a while “Skin Loneliness” rose to the top of the pile, but when I wrote the words “a certain loneliness” in the middle of an essay, I knew that was the title. Sure it has a certain amount of poetry to it, multiple meanings, and was descriptive of the contents, but mostly I chose it because it made me stop typing and as I reread the phrase the font enlarged and shifted to italics and then to bold in my imagination.

How did you know when your book was finished?

To this day when I read from my novel, which has been in print since 2014, I change things on the fly, so I’m not one to ask about finishing. But since, hopefully, I’m always figuring out how to be a better writer, I tell myself it makes sense to take advantage of any chance I have to rework old pieces. Nevertheless, I knew A Certain Loneliness was done when the last sentence read, “Today, however, I know who I am.” But I can’t guarantee I won’t change that at future readings.

Charis Books & More 10th Anniversary Party (1984)

In this book, you reference writers Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Audre Lorde and provide glimpses into your bookstore career. How have these writers and your reading life influenced your work?

I was that girl who was always in love with my school librarians and their libraries. The acetate smell of new books was my first high, and I still remember the way the silk of old dust from neglected books felt on my fingers. At home I’d read with a flashlight under the covers until my mother came in and threatened me with ruined eyesight, and at school my current book stayed hidden and open inside the math textbook I was supposed to be studying. Later in life, I’d call in sick to work to lie in bed and read a novel all the way through. Reading could soothe me or empower or educate or offer a desperately needed moment of escape. It’s a cliché, but reading did save my life (So my poor eyesight, bad math skills, and lying were worth it.) And I didn’t know it at the time, but reading widely and wildly was teaching me how to write.

I noticed that when I read other writers with a disability and suddenly their phrasing made it clear they were speaking to able-bodied people, it pissed me off. Why didn’t I count? Why was I excluded?

You often mention identity and political organizing in your book. What’s behind your decisions on when and how to write about identity and politics?

When I first started writing about disability in the 80s, I had the sense that if I just explained things well enough people (meaning able-bodied people) would “get it.” But I noticed that when I read other writers with a disability and suddenly their phrasing made it clear they were speaking to able-bodied people, it pissed me off. Why didn’t I count? Why was I excluded? I also realized that I had a different approach when writing about being a lesbian. Perhaps in the past it had been different, but now us gays knew we were real people with rights and all the feelings, and we lived our lives that way with no apologies, begging, or explaining. When I compared this to the way I wrote (pandered) to an able-bodied audience with pleas for understanding, it embarrassed me and I stopped.

Instead, I took a lesson from a common exercise used in beginning art classes. There’s a portrait Picasso did of Igor Stravinsky sitting in a chair. We were told to turn it upside down, maybe even put a grid over it, and learn to draw, not our idea of what an old man seated looks like, but small square by small square, just what we actually saw. I think that now I do whatever the equivalent of this is in my writing. So when an essay is threaded through with identity and politics, that’s because those themes arise organically from the situation or scene I’m describing rather than being a goal or some sort of agenda.

Of course, what I give up with this approach is the power to tell readers what they should think. So sometimes when I write what I consider a scene of triumph where with skill and imagination, I figure out how to do something amazing that a reader themself would probably never even try to do, their take away can be that my life is terrible and difficult. But what I gain with this approach is an unsentimental, accurate, often sensuous, sometimes funny portrait of a life.

What do you hope that readers will take away from your memoir?

For many memoirists, what we’re doing is writing into the silences the best we’re able. For those of us who had polio, the way we were taught to ignore, overcome, fit in, and always be silent about disability was considered a source of our strength, but now in our later lives has become the opposite. Already, I’ve heard of people who had polio as a child for whom just the cover of this memoir had them sharing stories with friends and family that they’d never told before. Those of us who had polio or have other disabilities also bring our valuable and timely skills of adapting, our senses of humor, and our experiences of living full lives in a world that tries to diminish us to the work we do in the world today.

Reading could soothe me or empower or educate or offer a desperately needed moment of escape…I didn’t know it at the time, but reading widely and wildly was teaching me how to write.

What’s something you’ve recently learned from reading?

Every book I read teaches me something. Vi Khi Nao and Aliesa Zoecklein’s poetry have taught me about the way imagery can lift writing up off the page. The over forty years of reading Ursula Le Guin is a lesson in imbuing dignity into all our characters. Carmen Maria Machado’s collection of stories reaffirmed for me the power of writing about the body, and Stephen Kuusisto’s memoir made me ache with recognition when he describes a young kid trying to pass as “normal.” Yaa Gyasi’s Homecoming and Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of the Sable Venus taught me about the authority of structure and naming, respectively. Cynthia Barnett’s Rain shows the power of a deep dive into a single subject, and Sarah Einstein’s writing is an example of how intellect and compassion are not opposites. The Prey of Gods by Nicky Drayden is a joyful romp of a book and reminds me that good writing includes having fun. And Michele Leavitt’s work on class and adoption makes me aware, over and over again, that I’ve held beliefs that are just wrong—a valuable lesson for a writer.

Are there particular conversations you would want to continue to have with your readers, off the page?

I always like to talk about sex, desire, and bodies with disabilities and the excitement of sexual relationships that require communication, experimentation, and a flexibility of imagination.

Even though it seems I’ve written a whole book about the tension between isolation and independence, I don’t have it figured out. And these days I’m married, which adds the complexity of maintaining independence within the expectations of giving and getting help within an intimate relationship. I need other people to tell me how they do this.