By Claudia Acevedo

Virtual Launch Event: McNally Jackson, Monday, June 15, 7pm EDT, with Jacki Lyden. Register here.

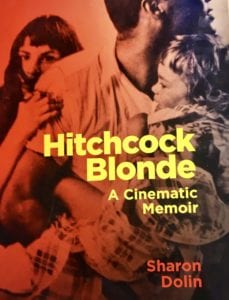

I was introduced to Sharon Dolin’s work by my thesis advisor while completing an MFA last year, so I was already a fan of her poetry before reading Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir (Terra Nova Press). A poet myself, I was particularly interested on seeing how her story unfolded in prose. It was an intense, yet rewarding, experience—seeing the similarities between our lives’ big catalytic absences, especially those brought on by a mother’s mental illness, dealt with such grace and emotional poignancy.

I was introduced to Sharon Dolin’s work by my thesis advisor while completing an MFA last year, so I was already a fan of her poetry before reading Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir (Terra Nova Press). A poet myself, I was particularly interested on seeing how her story unfolded in prose. It was an intense, yet rewarding, experience—seeing the similarities between our lives’ big catalytic absences, especially those brought on by a mother’s mental illness, dealt with such grace and emotional poignancy.

It’s easy to fall in love with this book. Ten Hitchcock films serve as the book’s framing device. She ingeniously weaves his filmography–a formative part of her childhood–and leading women into her own narrative, helping her paint a picture of what it was like to grow up in 1960s Brooklyn with a schizophrenic mother and traveling salesman father, and work through romantic and creative turmoil in her adulthood. Despite the difficult themes, Hitchcock Blonde is well-paced and engrossing, a vivid attempt at getting to the bottom of the “memory-wounds” that have shaped her art and who she is.

Amid this terrible pandemic and publisher deadlines, Dolin made the time to correspond with me via email earlier this year to discuss the memoir, the power of metaphor, and the relevance of Rear Window to our current way of living and connecting with others.

When the idea for writing a memoir through the lens of ten Alfred Hitchcock movies occurred to me, I leapt at the creative challenge it presented.

1. What called you to write a memoir at this particular moment in your career and life?

I have been writing poetry for many decades and I always like to set myself new challenges. When I began writing this memoir seven years ago, I was looking for a long-term project for writing about my life, but one that would, as Emily Dickinson advises, “[t]ell all the truth but tell it slant.” When the idea for writing a memoir through the lens of ten Alfred Hitchcock movies occurred to me, I leapt at the creative challenge it presented. I see my use of Hitchcock as akin to metaphor, where two things are compared that have similarities as well as differences. Of course there were formal challenges involved. How much should I switch back and forth between my discussion of the movie and my discussion of my life? I wanted to give readers two kinds of experience: intellectual as well as immersive. First, there is the aesthetic, intellectual experience of seeing, for instance, Miss Froy in The Lady Vanishes, as a metaphor for my vanishing mother. But then, I also wanted to give the memoir reader the emotionally immersive experience of being along with me the one time, as a child, I visited my mother in the psychiatric ward of a hospital and felt as though the mother I knew had vanished. Here, of course, both the aesthetic and the emotional should converge in the reading if I have been at all successful.

Sharon Dolin in 1981. Courtesy of the author.

2. What were some of the most challenging and surprising aspects of writing this book, both during the thick of it and after having a completed draft?

I was most challenged and surprised in the act of writing this memoir by those parts of my life I had avoided facing: the infidelities of my father, for instance, and the cocaine use of my fiancé. In working on Rear Window, the challenge of having to face the truth of my dad’s infidelities shocked me into awareness when I realized that there were similarities between Thorwald the travelling salesman and my father the travelling salesman. It took the writing of the chapter for me to make these chilling connections, regardless of how many times I had seen this movie before. The same was true for Spellbound, where I had to face my fiancé’s cocaine addiction as being much more pronounced and probably responsible for what I had previously never understood as psychotic behavior. It was through watching the threatening, violent, unpredictable behavior of Dr. Edwardes that I was able to reach this unhappy realization.

After completing the book and in revising it, I also came to acknowledge how much my being the daughter of a schizophrenic mother had shaped me and had influenced my relationship choices. Of course, these moments of discovery are what every writer is in search of, no matter how painful. I write to discover what I had not noticed or known before. And it was through the lens of Hitchcock that I was able to make these discoveries. Oddly, I doubt I would have been able to see my life as clearly if I had only looked at it directly. I cannot overstate the power of metaphor (the slanting gaze) as a way to make us see clearly.

3. Did you share sections of the book with family or people you wrote about? What is your policy for writing about people close to you?

As a writer, I have always felt that I had the right to write about anyone, even the people closest to me. I have always exercised that level of freedom in my poetry, for instance, writing poems about my mother’s schizophrenia in my first poetry collection Heart Work. I don’t go out of my way to show my writing to anyone, or to get their permission. The most I have done for this memoir is ask if they would prefer a pseudonym and I have changed almost all of the names, aside from my parents’, to protect the living and the dead. Most people have a narcissistic streak, I have found, and feel flattered to have themselves appear in my writing, even if it is not in the most flattering light.

Dreams are gifts to us from the subconscious mind, just as poems are. And when a dream recurs, I take it as a sign that something particularly potent wants to communicate itself to me.

4. Who is Hitchcock to you now? Has your perception of him/his work or anyone else featured in the book changed after writing the memoir?

I have had to learn, over and over again in my life, that there is a huge difference between the person and the creator. I think Hitchcock is a genius when it comes to filmmaking, but I think he was a deplorable man, particularly in his behavior towards certain women, such as Tippi Hedren, which I mention in my chapter on The Birds. I don’t think my attitude toward Hitchcock the filmmaker has shifted. I love his movies. I have always loved his movies, and even after repeated viewings, I can return to them in the same way I return to certain paintings and songs that I love.

My favorite movie remains Rear Window. And now that we are all caught on Zoom or Webex or some other on-line platform where our hunger for human connection has all made us voyeurs to some extent, the movie seems as contemporary as ever. Here I am, sheltering at home in New York City, where I find myself peering into the windows of those in the same meeting with me—very much the way Jeffries, caught inside his apartment with his broken leg, peers inside the rooms of his neighbors across the way. I don’t expect to witness a murder, but I do acknowledge the minor titillation of catching someone slightly off-guard as I am watching. Of course, if my video is live, I continue to have to grapple with that somewhat uncomfortable feeling that eyes are also upon me.

5. Dreamwork and recurring nightmares are featured prominently in the book. Could you talk about the importance of these subconscious patterns and their role in your work as a whole?

5. Dreamwork and recurring nightmares are featured prominently in the book. Could you talk about the importance of these subconscious patterns and their role in your work as a whole?

Dreams are gifts to us from the subconscious mind, just as poems are. And when a dream recurs, I take it as a sign that something particularly potent wants to communicate itself to me. Thus, it became a natural when I had hit upon the idea of writing a memoir using Hitchcock that I return to the recurring childhood nightmare I used to have in which Hitchcock’s truncated body figured. Writing that opening section, “Hitchcock in Brooklyn,” allowed me to do dreamwork on that childhood nightmare, and to make the connection between Hitch’s truncated body and other kinds of truncated and partial views in my childhood, as well as to suggest the larger point about memory itself always being a truncated and partial view.

And of course there is something dreamlike—or, rather, nightmarish—about many Hitchcock movies. So I am doing dreamwork on Hitch as much as I am doing dreamwork on my own dreams and, by extension, on my own life. Life is a dream, wrote Calderón, as the memoir reminds us.

In the Spellbound chapter, I record the poem that emerged out of a dream, another gift from my subconscious mind, where my mother and dead lover were connected. I think the poem, more than prose, is better able to gesture at the rudiments of desire: first for the mother and then for the lover.

At this point in my life, I don’t often remember my dreams, so I was thrilled when, after working on this memoir for so long, and right after completing a draft of Vertigo, the final movie I discuss in the book, that I should gift myself with a dream—a rather positive one—which I describe in the coda “Hitchcock in Manhattan.” Like most memoirs, mine does not focus on the moments of joy in my life, so I am particularly happy that my dream allowed me to end on a note of hope.

6. Where do you go from here? What is your next project?

Aside from working on poems, my next prose project will be as different in style and tone from this Hitchcock Blonde as possible. My next project is a memoir about dogs, which I began working on last summer, with the growing awareness that my 14-year-old dog was nearing his last days. It is a book with much greater levity—one that allows me to write about my life with dogs and my life as a parent and to draw some unusual—even amusing—parallels.

Sharon Dolin is the award-winning author of six poetry collections, most recently Manual for Living and Whirlwind. She is the recipient of numerous grants and awards, including the Witter Bynner Fellowship from the Library of Congress, the Gordon Barber Award from the Poetry Society of America and her translation work has been supported by Institut Ramon Llull and the PEN/Heim Translation Fund. Her fourth book, Burn and Dodge, won the AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry. Follow her on Twitter @SharonDolin and for more information visit her website: sharondolin.com. She lives in New York City.