By Timothy Hampton

Music and film fans were treated in early June to the Netflix release of Martin Scorcese’s new film about Bob Dylan’s 1976 tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue. The film features documentary footage of Dylan and his band in electrifying concert performances. That footage is framed by a set of interviews with both actual tour participants and fake talking heads, who comment on the events. By blurring history and fiction the commentary cleverly packages the tour as both chaotic and yet still relevant; it’s subtitled “A Bob Dylan Story.” Yet the clash of illusion and reality was already an essential part of the tour and contributes to its political meaning–both then, in the year of the American bicentennial celebrations, and now, in the age of Trumpism and Fox News.

By blurring history and fiction the commentary cleverly packages the tour as both chaotic and yet still relevant.

The Rolling Thunder Revue had Dylan traveling across New England, playing in small cities, Plymouth to Montreal. He was joined by a Who’s Who of fellow singers, including Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, and Joni Mitchell. The band included musicians such as the violinist Scarlet Rivera and the bassist Rob Stoner, who had made Dylan’s recent album “Desire” such a sonic delight. The choice of New England mill towns for the tour seems to have had a kind of spiritual-political intention. “Why would he play some place so small?” asks one of the fans in Plymouth, midway through the film. It was an encounter with a semi-rural America that was being depleted by a changing economy. The contemporary resonances with Trump’s claims to speak for a “real” America are, of course, unmistakable. But the illusion of freedom presented by the tour was already shot through with nostalgia. For the context for the tour is the cultural misery of the mid-1970s, when the the late-1960s hippie dream of freedom, funny clothes, and “the road,” had been brought up short by the reality of the defeat in Vietnam, Watergate, and a slowing economy.

The sense that the tour is a fiction (Dylan as gypsy) that is unfolding against another fiction (the glitzy surface of the bicentennial celebrations) is replayed in the iconography of the shows. Dylan’s floppy hat and white face-paint mimic the main character of Marcel Carné’s 1945 film about the Paris theater world, “Children of Paradise,” an art house favorite about the clash between reality and illusion. Carné’s film would form a loose template for Dylan’s own attempt to reshape the Rolling Thunder material in his 1978 film essay, “Renaldo and Clara.” But he had been quoting Carné as early as 1975, when the lyric to “You’re a Big Girl Now” had cited the heroine of the movie reproaching her lover, who cannot free himself from the fictions he has made about her identity, “Love is so simple.” Dylan, in makeup and headgear, here mimics Carné’s doomed character Baptiste, caught between the banal reality of family life and the romance of illicit passion–even as the singer’s jeans, vest, and boots turn him into some version of Billy the Kid from a Hollywood western. He is both artiste and bandido, exotic yet American. His carnival company and the powerful, shouted, vocal performances remind the post-1960s audience that the “real” America was a utopian collective that could still take shape—at least on the stage. Life may not, in the end, have turned out to be a magical mystery tour for many of Dylan’s listeners, but Dylan’s show reinvented the audience’s favorite stars, from Baez to McGuinn, as Children of Paradise in the American grain.

Paralleling the ambiguity of the spectacle were the new songs, taken mostly from 1975’s “Blood on the Tracks” and 1976’s “Desire.” The first of these albums looks back to the 1960s, recasting that era’s social unrest as a version of “On the Road.” The mad journeys depicted in such songs as “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Idiot Wind” both reflected Jack Kerouac’s beatniks and the later, less sublime, moment of hippie restlessness. Rolling Thunder reinvented these themes as a musical bus trip. Against the phony patriotism of the bicentennial events, Dylan’s group was digging deep into the bloody recent history of a wounded country.

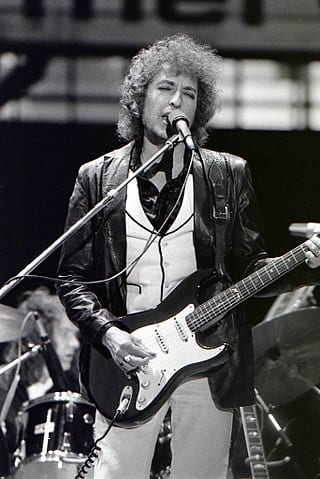

(Wikimedia Commons)

Yet these songs are offset by the songs from the recently released “Desire album,” which form the heart of the set list in the film. These songs, co-written mostly with Jacques Levy, have everything to do with the politics of Rolling Thunder and of Scorcese’s film. For the “Desire” album straddles the violent line of confrontation between dream and reality, fantasy and brutal fact. “Desire” features a set of narratives of wandering and romance–songs about the south seas, the Klondike gold fields, Mexico, gypsy camps. Dylan’s stage act, with its gypsy flavor and exotic outfits, performs what the songs are about. Yet at the same time, for every tale of exotic beauty on “Desire” there is a tale of brutality or disillusionment, bringing us back to the desperation of the mid-1970s in the “real” America. Thus the mythical romance “Isis” (“a song about marriage,” as Dylan says at one point) stands over against the domestic drama of “Sara,” a tune written for Dylan’s soon-to-be-ex-wife, begging her not to leave him. Similarly, the romanticism of “One More Cup of Coffee,” which depicts a beautiful gypsy woman whose clan is ruled by a knife-wielding king, runs up against the brutal sociology of “Joey,” a tune about a Mafia clan ruled by an “old man” and his sons. This confrontation of enchantment and disenchantment haunts the album and makes it particularly difficult to read. We find it again on “Mozambique,” a tune about jet setters on the beach recorded at a moment when the the African country had just achieved independence from Portugal after a brutal ten-year war. And, of course, it is central to “Hurricane,” Dylan’s account of the framing of the boxer Ruben Carter for murder. (Carter appears in a contemporary interview wearing a wide-brimmed hat of his own, almost like a parody of Dylan’s festooned Stetson from 1976). The fact that Carter’s story unfolded in Paterson, New Jersey, the site of William Carlos Williams’s American epic poem “Paterson,” made the bicentennial background to “Hurricane” all the more cogent. No less important, the harmony and groove of the tune hark unmistakably to Dylan’s own earlier hymn to poetry and art, “All Along the Watchtower” of 1967. That song, with its “Joker” and “Thief” pointing ahead to the circus-like atmosphere of Rolling Thunder and Desire, here runs up against the brutality of life in the streets. The allegorical medieval castle that ends the song–the site of the famous “Watchtower”–is swept away by the vision of what happens to real boxers, in real landscapes: “In Paterson, that’s just the way things go,” sings Dylan. “If you’re black, you might as well not show upon the street.”

Dylan is asking us to think about what happens to the dreams of American romance in a world of military disasters and framed boxers.

The point here is that the play of fantasy and reality that shapes the Rolling Thunder Revue is part and parcel of both the moment of its creation (the glitzy surface of the Bicentennial overlaying the despair following the recent defeat in Vietnam) and the songs that make up the performances. Dylan is asking us to think about what happens to the dreams of American romance in a world of military disasters and framed boxers. His exotic persona–in white face, peering out from under the floppy hat–seems now like a heroic attempt to replace anomie with magic. The disillusionment of 1976 is sublimated into Dylan’s gypsy identity, which labors to resolve violence and romance. That dialectical effort is, in turn, reworked forty years later, with Scorcese’s introduction of phony talking heads and grandiose commentary. Halfway through the movie Michael Murphy turns up, pretending to be the fake politician he played on the “reality” TV series “Tanner ’88.” The implication is that in 1976 Dylan tapped into something “essential” in America–but that it can now only be delivered as a cinematic joke.

Every event in American history returns as show business at some point. Even when we try to think about the limits of illusion and romance we can only do so through the prism of yet another form of fiction. This American fact haunts the project of the film and the concert tour. It is condensed in a single detail that emblematizes the whole project. Near the end of the film we see Dylan visiting Ruben Carter in jail. Dylan is trying to raise support for a man who has been falsely imprisoned. This is the American echo of Emile Zola’s accusation of the French government in the Dreyfus Affair–an instance of a great artist stepping up to defend the innocent. We are dealing with life and death here. It is serious business. And yet Dylan shows up for the meeting in his floppy buckaroo hat, adorned with flowers. He is never out of costume, even when someone else’s life is on the line. The moment encapsulates the interplay between fantasy and reality, show biz and political violence, that the tour and the film both chronicle and struggle to resolve. Show biz, as always in America, wins out.

Timothy Hampton teaches literature at the University of California, Berkeley. A scholar of the romance languages, focusing primarily on the Renaissance, he has written widely about literature and culture. His recent book, Bob Dylan’s Poetics: How the Songs Work, was published this year by Zone Books. For more information, please visit his website timothyhampton.org, where this essay also appears.