A Boat to Lesbos: and other poems centers on the Syrian migrant crisis. In this collection, the Syrian-British poet Nouri Al-Jarrah explores Arab diaspora through mythology and lyric representations of the Syrian refugee crisis. He composed the poems during the height of the crisis, from 2015-2016, and wrote the final poems in Lesbos and Athens.

A Boat to Lesbos: and other poems centers on the Syrian migrant crisis. In this collection, the Syrian-British poet Nouri Al-Jarrah explores Arab diaspora through mythology and lyric representations of the Syrian refugee crisis. He composed the poems during the height of the crisis, from 2015-2016, and wrote the final poems in Lesbos and Athens.

Al-Jarrah’s work is unmistakably contemporary and for the public record.

The collection is split into the titular epic poem and a string of standalone poems on the same subject. In “A Boat to Lesbos: Elegy to the Daughters of Na’sh,” Sappho and the poet call to the refugees in eight tablets, and members of a modern chorus of refugee “voices” respond, as in a Greek tragedy. The two “(Call of Sappho)” sections bookend the long poem with Siren-like artifice and authority. The Sappho-speaker’s lyrics alternately obscure the migrants in figurative language (“Like mermaids born in the quivering light”), turn to the surreal and horrific (“I sent my neighbouring sisters carrying water. They took it to the beach and returned with a boy they said was sleeping. When they laid him out on the sheet we saw he had no face.”), and issue direct warning (“You fight for life on the boats, and the sea swallows you before you land in Lesbos, while I die in Sicily fleeing home. Don’t believe Poseidon or Ulysses’s ship. Don’t believe the letters and don’t believe the words.”)

“I sent my neighbouring sisters carrying water. They took it to the beach and returned with a boy they said was sleeping. When they laid him out on the sheet we saw he had no face.”

Each response is a “Voice,” presented as an individual “I” but seemingly collective under the repeating title. One voice echoes Sappho’s birth metaphor and the poet-speaker’s self reflexive gestures, asking “Why did you give birth to me inside this book and leave me wavering in my fate.” Representation and re-creation are tied together in the poet’s use of the persona to show land and sea, writer and vulnerable subject.

This book—his first translated into English—was first published by the Milan-based al-Mutawassit Press in 2016 and has been translated in French, Spanish, and Italian. In 2018, Banipal Books published the English version, co-translated from the Arabic by Camilo Gómez-Rivas and Allison Blecker.

In the poet-speaker’s tablets, the lens roams from the island to the sea to Damascus, from myth to personal history and the near present. With such a ranging perspective, Al-Jarrah can enter the hypothetical: “And what if I had stayed that boy with the brown sandals and the yellow shirt and the sun in his words washed and pinned on a clothes-line.” Had he stayed in Syria, where would he be? The poet-speaker identifies with the migrants’ trials while suggesting and sometimes showing that he is grounded in safer circumstances. Al-Jarrah marks the end of the poem “London, Summer 2015 – Winter 2016,” so that his work is unmistakably contemporary and for the public record.

Some of the later poems repeat this technique, the place and date giving these poems a diaristic quality. In the location stamps, the poet can be seen traveling from London to Lesbos to Athens. The others engage with persona, invoking Telemachus and Odysseus.

*****

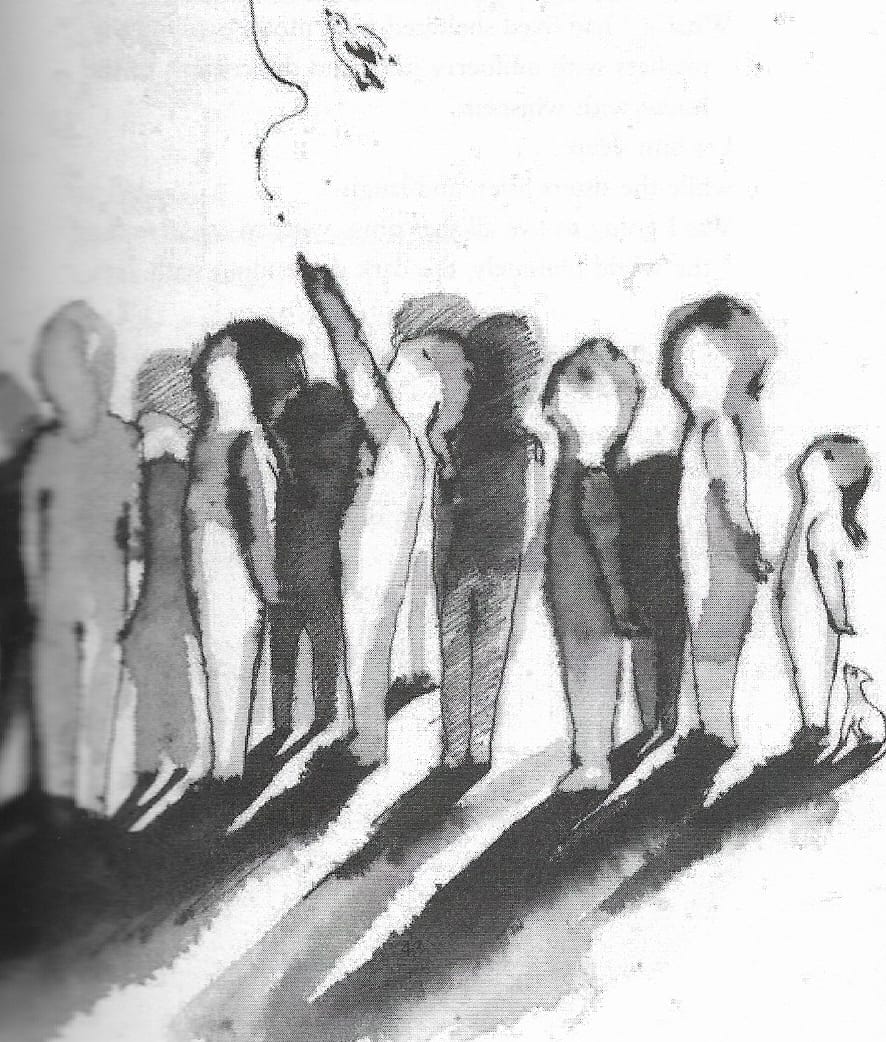

Born in Damascus, Nouri Al-Jarrah moved to London in the 1980s and began publishing books in the 1990s. His prolific body of work has been translated into several Asian and European languages. This book—his first translated into English—was first published by the Milan-based al-Mutawassit Press in 2016 and has been translated in French, Spanish, and Italian. In 2018, Banipal Books published the English version, co-translated from the Arabic by Camilo Gómez-Rivas and Allison Blecker. This edition is illustrated with paintings by Reem Yassouf, each rendered in black and white and mingling with the text. Ranging from female figures in water to children flying kites, the artist subjects are an apt pairing with the Daughters of Na’sh and the lost youth that appear in the poems. In an early note, Al-Jarrah explains that in Arabian mythology Ursa Major, or the Big Dipper, is envisioned as four daughters carrying their father’s coffin, with three other daughters trailing behind. Thus, Al-Jarrah blends Greek and Arabian traditions.

Born in Damascus, Nouri Al-Jarrah moved to London in the 1980s and began publishing books in the 1990s. His prolific body of work has been translated into several Asian and European languages. This book—his first translated into English—was first published by the Milan-based al-Mutawassit Press in 2016 and has been translated in French, Spanish, and Italian. In 2018, Banipal Books published the English version, co-translated from the Arabic by Camilo Gómez-Rivas and Allison Blecker. This edition is illustrated with paintings by Reem Yassouf, each rendered in black and white and mingling with the text. Ranging from female figures in water to children flying kites, the artist subjects are an apt pairing with the Daughters of Na’sh and the lost youth that appear in the poems. In an early note, Al-Jarrah explains that in Arabian mythology Ursa Major, or the Big Dipper, is envisioned as four daughters carrying their father’s coffin, with three other daughters trailing behind. Thus, Al-Jarrah blends Greek and Arabian traditions.