By Jeremy Wang-Iverson

The Believer Launch Events (Online):

New York City: Shakespeare & Company, March 15, 2021, 6:30pm (with Leslie Kean).

Los Angeles: Skylight Books, March 17, 2021, 6:30pm (with Dan Aykroyd).

In The Believer: Alien Encounters, Hard Science, and the Passion of John Mack, prize-winning New York Times reporter Ralph Blumenthal tells the story of how renowned Harvard Medical School psychiatrist John E. Mack became fascinated with a range of paranormal phenomena ranging from alien abductions to UFOs to past lives. Blumenthal interviewed dozens of Mack’s friends and colleagues, and conducted years of archival research, to understand what drew Mack to the fringes of science—and what he learned there. Blumenthal answers some questions about The Believer, which will be published in March by High Road Books, a new imprint from University of New Mexico Press.

In The Believer: Alien Encounters, Hard Science, and the Passion of John Mack, prize-winning New York Times reporter Ralph Blumenthal tells the story of how renowned Harvard Medical School psychiatrist John E. Mack became fascinated with a range of paranormal phenomena ranging from alien abductions to UFOs to past lives. Blumenthal interviewed dozens of Mack’s friends and colleagues, and conducted years of archival research, to understand what drew Mack to the fringes of science—and what he learned there. Blumenthal answers some questions about The Believer, which will be published in March by High Road Books, a new imprint from University of New Mexico Press.

How did you first learn about John Mack, and what made you want to write a book about him?

As the New York Times correspondent in Texas in 2004, I happened to pick up a used copy of Mack’s second book, “Passport to the Cosmos,” and was intrigued. What was an eminent Harvard psychiatrist doing investigating UFOs and aliens? The mystery that gripped him rubbed off on me.

John Mack was widely known in his time but seems to have largely been forgotten since his death. Why is that?

He was a colorful contributor to his own legend. The media gravitated to him. That largely dissipated once he was gone. And while he shed light on the mystery that consumed him, it remains unsolved.

We’re far from answering all the riddles in the cosmos. I have not abandoned my journalistic skepticism, but I’ll go with Philip K. Dick: “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

Why did Mack risk his academic reputation by deciding to study people who claimed to experience alien abductions?

Having stumbled across one of the greatest scientific mysteries of all time, he was too principled to simply turn his back. He was genuinely curious and relished the publicity and the controversy. And his stepmother had taught him never to run away from a fight.

How did Mack’s views about the nature of these abductions change over time?

After he ruled out all other possible explanations (mental illness, hoaxes, delusions, publicity-seeking, etc.), Mack soon concluded that his so-called experiencers were telling the truth and that abductions were a distinct category of anomalous events that had actually occurred in some definition of reality. Later he came to see them as among a range of mystical experiences that could not be proven and were not necessarily to be taken literally in our physical reality.

What role did Budd Hopkins play in Mack’s life and research, and how did their interpretation of alien abductions differ?

Hopkins was an accomplished painter and sculptor whose spotting of a UFO turned him into the first notable abduction researcher. Mack’s visit to Hopkins in 1990 exposed Mack to the bizarre accounts of abductees and he quickly assembled his own study group. But Hopkins always believed in the physical reality of the encounters. Mack grew to question them, uh, alienating Hopkins. But the two reconciled before Mack’s death.

Why did the Harvard administration react so harshly to the publication of Mack’s first book about alien abductions? What were their concerns about his clinical work and psychiatric research?

Harvard was home to lots of unconventional research but Mack’s high profile with a subject so derided by mainstream science and academia embarrassed medical school superiors. They felt pressured to investigate his research methods and seeming lack of scientific detachment. Unfortunately they convened what looked like a secret inquisition. Mack and his lawyers waged a fierce struggle for exoneration and Harvard ultimately cleared Mack of any wrongdoing.

In 2017 you helped break the New York Times story about a secret Pentagon program dedicated to analyzing UFOs. How did that story, and your subsequent reporting on the Pentagon effort, influence this book?

It was more the other way around. I knew from my research into John Mack since 2004 about the government’s long and checkered history tracking and covering up the UFO phenomenon. That helped me understand the significance of the Pentagon’s serious new interest into what became known as UAP, Unidentified Aerial Phenomena. But our Times stories never dealt with aliens or abduction. We had to stick to more veritable information like the Navy’s detection of the mysterious flying objects.

How did Mack’s interest in paranormal phenomena connect with his political activism—his involvement in the anti-nuclear campaign, his advocacy for Israeli-Palestinian peace, and other leftist causes?

There was a pattern to Mack’s odyssey, as I say in the book – a progression of passions from community health reform to Lawrence of Arabia, Middle East peace, nuclear disarmament, cosmic consciousness, alien life, and ultimately life after death. Holotropic Breathwork opened Mack to alternate states of consciousness. As he himself put it, Esalen “put a hole in my psyche and the UFOs flew in.”

Did you find yourself becoming more skeptical or less?

That’s hard to say. I believe (there we go again with belief) that Mack was onto something. We’re far from answering all the riddles in the cosmos. I have not abandoned my journalistic skepticism, but I’ll go with Philip K. Dick: “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

What is John Mack’s legacy? How should he be remembered?

As the flawed hero of a mythic journey. As I say in the book, he set forth, journeyed far, had many adventures and returned to tell the tale around the digital firelight, for humanity’s sake.

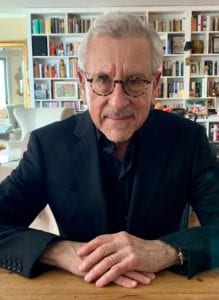

Ralph Blumenthal was an award-winning reporter for the New York Times. He coauthored the Times article in 2017 that broke the news of a secret Pentagon unit investigating UFOs, and he is the author of four nonfiction books including Miracle at Sing Sing: How One Man Transformed the Lives of America’s Most Dangerous Prisoners. A distinguished lecturer at Baruch College, he lives in New York City. For more information, visit his website: ralphblumenthal.com