Earlier this spring, Potomac Books, an imprint of University of Nebraska Press, published My Dear Boy: A World War II Story of Escape, Exile, and Revelation by Joanie Holzer Schirm. This is Schirm’s second book, following Adventurers Against Their Will, that draws on her father’s past, after she discovered a collection of letters at the time of his death in 2000. In My Dear Boy, Schirm writes in her father’s voice, creating the memoir he might have written, based on her extensive research and reading closely his correspondence that she arranged to have translated into English from the original Czech. Oswald “Valdik” Holzer was a Czech Jewish doctor who escaped Prague in 1939, seeking refuge in Shanghai, before moving to the United States and settling in Florida, where Schirm was raised and lives today. This interview with Schirm, just below the book trailer, continues a Q&A that appears on the University of Nebraska Press blog.

In addition to gaining a deeper knowledge of your father, what changed for you after writing My Dear Boy?

In a small Florida town, I was born into a life of ease and privilege and raised in my mother’s Christian faith. I had no personal experience of prejudice and little awareness of what my father had endured. During the past decade, as I’ve researched the lead-up to World War II and subsequent atrocities, I’ve witnessed the alarming erosion of protections for human rights and dignity. The global migrant crises made up of desperate people like my displaced father has exploded while echoes of the 1930’s slip from the mouths of dangerous new autocratic leaders. It’s clear it’s not limited to anti-Semitism but a fear of the ‘other’ which incites violence. As I’ve now walked within the Holocaust’s multi-layered shadow that accompanied my father’s life and now mine, from a place of knowledge, I feel an obligation like never before to speak the truth against hatred and persecution. As my grandfather, Arnošt wished, as a benefactor for suffering humanity, I have the extraordinary opportunity to bear witness for those who came before us and forge ahead against backward pressure.

Schirm’s father, Oswald “Valdik” Holzer, in 1938.

A lot of the book is about concealing the truth in order to spare the people we love. Were there things that you left out of the book for the same reason?

No. To ensure the reader gains the most from my father’s compelling account, I included his most excruciating truths that he’d hidden from my brother, sister and me. Not wanting to bring us children fear and sorrow, his silence also allowed him to avoid a revisit of his own pain and guilt. By not hiding his most painful revelations, I inherited his heartache as I believe was meant to be. Sharing it this way, the complete story is revealed through the words of his own correspondence and my later research to determine who lived and who died. I have no doubt he carried heavy guilt during the remainder of his life about his failure to save lives. From my findings, I believe he did all he could have done under the circumstances, with the knowledge he held at the time. It was clear his real experience offers modern relevance for creating empathy for the everyday frantic life and death decisions of forcibly displaced persons, migrants, and refugees.

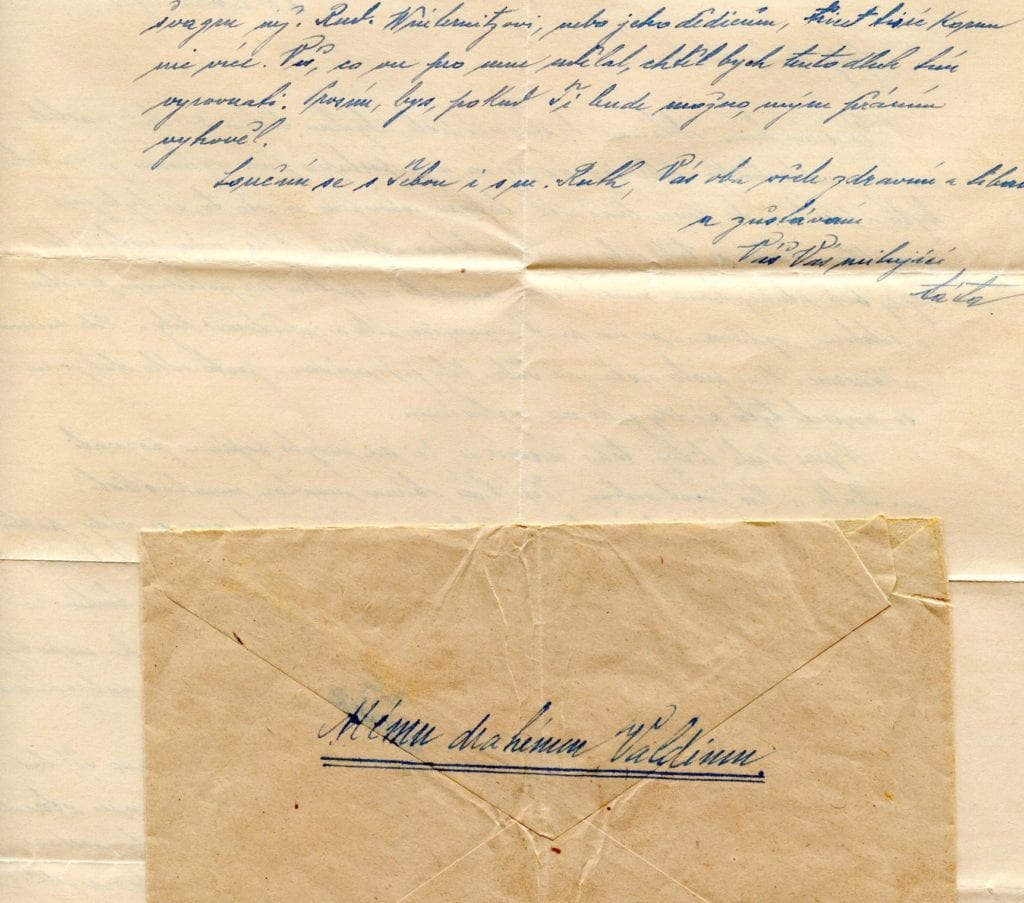

The last letter Valdik Holzer received from his father Arnošt (Schirm’s grandfather) – the title MY DEAR BOY refers to this letter.

What do you think your father would make of current immigration detention centers in the U.S?

My father would be appalled by the actions of his adopted country. The erosion of government accountability that characterized the Third Reich echoes the insufficiently conceived prison- like facilities to prevent foreigners from entering the country. The centers, unresponsive to protecting asylum seekers, create terrible trauma, especially for children when separated from their parents. These actions are contrary to fundamental American principles which my father proudly exemplified by hosting at our home a Cuban refugee family in the 1960s. I also know from conversations with both my parents what they thought of the relocation and internment of 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent. With no evidence of these citizens’ disloyalty, my parents thought it was a disturbing example of racist persecution by the fact that citizens who traced their ancestry to America’s other WWII enemies, Germany or Italy, weren’t incarcerated. Recalling the media fanning the flames of fear in America, my father said it reminded him of why public opinion turned negative in 1930s Czechoslovakia as Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi oppression flooded their border.

Joanie Holzer Schirm and her father Valdik in 1996.

My Dear Boy is the story of your father’s escape from persecution as a Jew during World War II, but you do not share his religion, being raised in your mother’s Christian faith. Did you gain a greater appreciation for the Jewish culture as you wrote the book? Did you feel you were approaching the story as an outsider?

With feet in two heritage camps, curiosity about faith and tradition propels me. Not only did I want to learn about my father’s Jewish cultural past but also how my Christian mother first and foremost was comfortable to teach and to offer a “Christian way of life” rather than to proselytize. Initially, more onlooker than outsider, as I waded through brutal Holocaust history, I developed a much broader view of what took place. My writing mission moved from dissecting my parents’ situation to working to universalize what happened to millions and make it felt. Through unadorned delivery of their story emerged an emotional chronicle that offers a retort to the Nazi’s crazed dehumanization of humanity. Background true stories reinforce the Nazi-fixation to destroy the Jews and others they deemed inferior. The reader is reminded that victims are more than statistics and empathy is neither place nor time limited. With feet firmly planted in Holocaust education, exhibitions around the world share my father’s story, and I participate in teacher training institutes and in Orlando as a capital campaign co-chair for the new Holocaust Museum for Hope & Humanity.

Joanie Holzer Schirm was the founding president of Geotechnical and Environmental Consultants, Inc., in Orlando, Florida, which she directed for seventeen years. She is now a full-time writer, speaker, and curator of the Holzer Collection, her father’s World War II legacy. Schirm is the author of Adventurers Against Their Will: Extraordinary World War II Stories of Survival, Escape, and Connection—Unlike Any Others, winner of the Global Ebook Award for best biography. For more information, visit her website: www.joanieschirm.com.