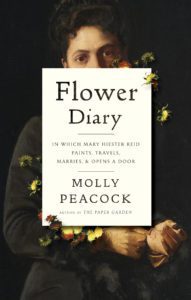

“Perhaps the most interesting thing here is that Peacock is incapable of writing a dull book … Reading a book by Peacock is like listening in on a fascinating conversation … Peacock is also the type of writer who insists on a physical book being as memorable as its contents. With its heavy stock, beautiful colour reproductions, and elegant floral endpapers, Flower Diary really is in a league of its own.”

“Perhaps the most interesting thing here is that Peacock is incapable of writing a dull book … Reading a book by Peacock is like listening in on a fascinating conversation … Peacock is also the type of writer who insists on a physical book being as memorable as its contents. With its heavy stock, beautiful colour reproductions, and elegant floral endpapers, Flower Diary really is in a league of its own.”

— Literary Review of Canada

We are pleased to share this interview with Molly Peacock, poet and biographer, talking about her recent book Flower Diary: In Which Mary Hiester Reid Paints, Travels, Marries & Opens a Door, published this past fall by ECW Press. Below please also finds audio interviews with the Skylight Books podcast (in conversation with Donna Bailey Nurse), the Art Curious podcast, and a Zoom presentation with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts that was held on October 4, 2021, the 100th anniversary of Mary Hiester Reid’s death.

When did you first come across Mary Hiester Reid and her artwork? How did the idea for the book come about?

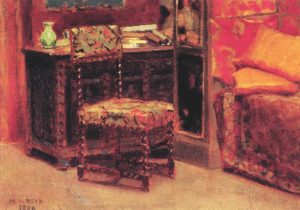

After I finished The Paper Garden, I was looking around for another project and started researching the lives of North American women botanical artists. It was very frustrating; so little is known about their personal lives. When the Art Gallery of Ontario called and asked me to speak about a single painting in the collection, I shot back, “Got any 19th-century flower paintings by women?” thinking that perhaps I’d get a botanical lead. Instead, a curator led me to Mary Hiester Reid’s painting, A Study in Greys. “Wow,” I said, “look at all the triangulation in this painting! Three objects, three sets of roses…the painting has three areas vertically, three horizontally… Then the curator told me that MHR more or less willed her husband to a younger painter, her former student—and that her husband married that younger painter less than a year after she died. I’m in, I thought. Who was this woman?

Can you talk about your research into the daily life of a woman during MHR’s time?

Researching MHR’s daily life was a lot of fun. I looked at the newspapers of her time, especially the ads for “women’s” items, like corsets. I also looked at the cookbooks she might have used and the minutes of art organizations of her time. I checked out advice manuals, especially birth control advice, travel advice, etiquette and manners. I walked around the neighborhoods she lived in, seeing buildings that she might have seen, squeezing myself into perspectives she would have shared in the Catskills, Paris, Madrid, Philadelphia and Toronto. Eventually, I found myself at certain moments feeling as if I were looking out of her brown eyes.

What is the importance of including some of the philosophical ideas that were forming while MHR was making her art?

I didn’t intend to get into the philosophy of art and ideas of empathy. But as I followed the mystery of the sources of the phrase “sympathetic realism,” and as I discovered links between theories of painting and nascent psychological ideas of projection, I knew I had to. It was fascinating, and I wanted my readers to have the pleasure of weaving those threads of thought. When I was in my early twenties, I was entranced by philosophy, and it was a delight to re-enter a world I had once abandoned.

In reference to the book’s title, can you give us a sneak peak into the door that MHR opened? Mary Hiester Reid opened our door to being able to balance making a marriage (because marriages constantly have to be re-made!) and making art. She also opened the door to optimism in a world that was going against her at every turn.

How does this book act as a companion to your previous one, The Paper Garden?

Flower Diary, like The Paper Garden, is about a valiant, intriguing woman artist from another century whose life has amazing relevance to us today. Flower Diary leaps to the 19th century in North America, whereas The Paper Garden took place in the 18th century in England and Ireland. Both books are fully-researched and documented, but they are structured uniquely. They each use an artwork at the beginning of every chapter, brief meditations about creativity, and bits of my own life as I track down these lives of the past. And best of all, both books are beautifully produced. The layout and the illustrations are divine! I had the same awesome editor for both books, Susan Renouf. Our intuitive editing process allowed the books to become companions.

- Still Life with Daisies

- Light Studio in Paris

- Nasturtiums (1910)

- Into the Forest

Flower Diary was hard to research. Why did you tackle it?

Hey, if we always had an easy route to discovery, that would that mean lives of underrecognized people would never get rediscovered. I met Mary Hiester Reid through her splendid images. Once I started following her, I realized that many of the places she lived and travelled to still exist—and I actually live near some of them. Then I discovered that she wrote a travelogue–and that several of her key letters were preserved. I was able to follow her to Paris and Spain. After that I realized that I had accumulated images, places, a piece of long-form journalism—and a biography about her husband that contained information about her. Most importantly, I read, then met, valiant art historians who had tracked down all of Mary’s reviews and a poignant essay written just after her death. As the type of biographer who loves to unearth talents of the past, I quickly learned that not only words document lives–images speak, too. The fog had lifted…

Can marriage and creativity mix? Does Flower Diary hold answers?

As a lifelong student of creativity, I’m so curious about how people manage their processes. In our western culture that values commerce over art, it is very hard to stake out a path to a creative life. Deep, rich relationships are also necessary to the richly lived creative life. Mary Hiester Reid was in the first generation of women to be married and a serious artist. I actually think the way she did it was with a sense of humor. She tolerated her husband’s roving eye, made friends with the object of his affections, but also grabbed his hand and left town when the emotions got too intense. All the while, with his support, she was expressing her multitude of reactions to the world in her paintings themselves, her flower diary. Here we are, a century and a half later, and it’s still incredibly difficult to maintain a marriage and a serious artistic career. We all can learn a lot from Mary Hiester Reid—and adopt her motto of persistence: “get cheerfully on with the task.” She stuck with her marriage, watching its energy ebb and flow, and allowing her art to grow and change along the way.

In both of your biographies, you include the life of the biographer as she tracks her subject. But many view biography as impersonal—solely based on the facts. How did you arrive at your technique?

I am always curious about the voice of the biographer beneath the sentences of a biography. Why did the biographer choose the subject? What is the relationship between them? How is the biographer framing the questions about the times the person lived in? Yes, a biography is factual, but biographers shape every sentence. The rhythm of thinking and the cadence of language reflect the biographer’s personality at every clause. That makes every biography personal, despite the walls of information the biographer constructs. If a biographer reveals herself and her motives, then she adds another layer to the tapestry of how we look back at lives from the past.

Flower Diary really is a triple biography, of Mary Hiester Reid, her husband George Reid, and their student (George’s second wife) Mary Evelyn Wrinch. When did you know that you were really writing about three people?

These people were so intertwined that I just couldn’t keep them artificially separated

Couldn’t you just say it was a love triangle and be done with it?

Whoops, this isn’t a novel—though I hope it sweeps along like one. I will never ever know exactly what went on among the two Marys and George. What I try to convey is the subtlety and complexity of their relationships over time, especially as expressed by the sensuous threesomes of flowers that Mary painted. Let’s say they ultimately lived in an atmosphere of a menage à trois.

Not only is Flower Diary a triple biography with spots of memoir, it’s also about creativity itself. Because there are so many strands in the book, how did you decide to weave it?

I had a terrible time! How was I going put Mary Hiester Reid front and center, add information about her husband, George Agnew Reid, layer in the life of their student Mary Evelyn Wrinch, introduce the ideas of the thinkers who were developing theories of empathy, all the while allowing the reader into my footstep process, as my husband and I were tracking them down? After many tussles with the text over a number of years, I decided to introduce each chapter with an image from a painting or drawing by one of them, and to follow the chapters with Interludes. The interludes let the book switch gears without interrupting the flow.

In our western culture that values commerce over art, it is very hard to stake out a path to a creative life. Deep, rich relationships are also necessary to the richly lived creative life.

Flower Diary quotes poems from American Emily Dickinson to British Robert Browning to Canadian Elise Partridge. Why is poetry important to your biography process?

I came to biography from poetry, and my understanding of the creative life is from writing poetry. Mary she produced paintings that were often described as poetic in styles that often attached to the poetic. Plus, Mary was a reader of poetry. It was natural to allow my other art in.

Mary Hiester Reid was a member of several artists communities. What’s so important about Art Colonies?

Community, of course. What Candace Wheeler, associate of Louis Comfort Tiffany, showed to Mary in the art colony Onteora, was a way of working in loose community with other artists. Mary spent seventeen summers there. Art colonies such as Onteora, or the Cite Fleurie where Mary lived for a year in Paris, were marvelous inventions of the 19th century, providing the stimulation, friendships, and freedom from everyday demands that allowed her painting to flourish. She and her husband George Reid were able to replicate that in their Wychwood Park community in Toronto.

Can you talk about how travel influenced Mary Hiester Reid?

Mary travelled five times to Europe, sometimes on budget steamship lines, to absorb the Impressionist vision in Paris, the Tonalist vision in London, the still life and the figure in Madrid and the interiors in paintings in Amsterdam. Painters she revered, like Whistler and Velazquez, were palpably present to her. She was always learning and absorbing. Travel was also a way to spring from the constraints of her wifehood, renew her marriage by being with her husband as two on the road. Travel wasn’t easy in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but MHR packed her paints—and her travel dress—to sail across the Atlantic, sometimes in roiling waves, to enter into the sublime dislocation that allowed her vision to expand. Travel was a way for a corseted artist to develop in freedom.

“Part memoir, part biography, this is a beautifully written and layered volume that opens its arms wide and encompasses art, domesticity, the intimacy of marriage and of death. Lush and beautifully produced.” — Toronto Star

Given the fact that your husband was so ill while you were writing Flower Diary, how did you handle your caregiving and your writer/researcher responsibilities?

The truism of that announcement on an airplane that you must put your own oxygen mask on first, before you help others, is also the motto of caregiving. I’m a writer, and I just have to write to anchor myself. So, in the midst of the phone calls from hospitals, and my husband’s appointments, which he largely navigated on his own till the last three months, I would dive into the 19th and early 20th centuries. What a fabulous relief and contrast—yet what an interesting comparison—to pandemic life in the 21st. It is delicious to live for a while in the past, a world of horse-pulled streetcars, steamships, handsewn dresses, and milk in glass bottles with cream on the top. But the sexism of Mary Hiester Reid’s day only highlighted the fabulous sexism that female-identified caregivers face today. Wives are expected by physicians, nurses and hospital workers to shoulder colossal burdens. If a wife in a traffic jam arrives 15 minutes late, she has fallen down on her job! If a husband manages to stroll onto on a hospital floor to visit a wife, everyone bows down as if to a saint. Wives are invisible—and not always listened to or taken seriously. All too often there were occasions when I accompanied my husband to a medical appointment or procedure that offered me, as someone ignored but responsible, a glimpse into Mary Hiester Reid’s invisibility and silence. I am so glad she had her paintings to speak for her! And so glad that my own husband understood how important it was that my writing bolster me so that I could be there for him. He tried every day to lessen demands on me. When I am at the end, I only hope I can be as gracious as he was.

Molly Peacock is a widely anthologized poet, biographer, memoirist, and New Yorker transplanted to Toronto, her adopted city. Her books of poetry include The Analyst, The Second Blush, and Cornucopia: New and Selected Poems, 1975-2002. Her prose includes an earlier biography The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life Work at 72 and a memoir Paradise, Piece by Piece. For more information, visit her website.

Molly Peacock is a widely anthologized poet, biographer, memoirist, and New Yorker transplanted to Toronto, her adopted city. Her books of poetry include The Analyst, The Second Blush, and Cornucopia: New and Selected Poems, 1975-2002. Her prose includes an earlier biography The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life Work at 72 and a memoir Paradise, Piece by Piece. For more information, visit her website.