Love, Loosha: The Letters of Lucia Berlin and Kenward Elmslie. Edited by Chip Livingston. High Road Books, $29.95 (312p). Publication Date: November 2022.

“Livingston (Owls Don’t Have to Mean Death) delivers a revealing collection of letters between short story writer Lucia Berlin (1936–2004) and poet and lyricist Kenward Elmslie (1929–2022)…their correspondence makes for an intimate, touching portrait of a friendship, one bound by a love of literature.” –Publishers Weekly

“This book, the correspondence of two good writers and close friends, presents completely new material written very well and at the same time in a comfortable and natural style. The letters are personal, warm, witty, imaginative, detailed, sometimes lyrical, and, most compellingly, written with frankness, honesty, and good humor. Here, we can look ‘behind’ their art and witness what goes on in their day-to-day lives, how they experience moments of joy or well-being, how they suffer and try to laugh off their suffering. Above all, the compelling pleasure of the book is the opportunity to spend personal, intimate time in the company of these lively, intelligent, compassionate, and mutually loving people.” —Lydia Davis

(High Road Books, November 2022)

As a former student of Lucia Berlin’s and a long-time personal assistant to Kenward Elmslie, you were in a unique position to edit a collection of their letters. How and when did you begin working on the project?

I’d known during Lucia’s life how dear, and well-written, she considered Kenward’s weekly letters to her. She read from his letters in our creative writing classes, showed me his postcards and letters that were displayed on her refrigerator when I visited her homes, and Lucia often talked about, and wrote to both Kenward and me about, the fact that they should be published. When I began working for Kenward, I quickly learned that the feeling was mutual; he treasured and thought the world of the letters Lucia wrote to him, which I often delivered from the mail slot in New York or the post office in Vermont. At Lucia’s funeral service in December 2004, her sons gave me a few bags of the letters Kenward had sent her, saying if there ever were a published correspondence that they didn’t want these to be lost, so the idea had been percolating for awhile that it might fall to me to see that their correspondence was shared publicly. I spoke to Lucia’s sons and the guardians of Kenward’s estate in March 2019 with the formal idea to start typing up the letters, and then it took about three full years of gathering, transcribing, selecting, and editing material for the contents of Love, Loosha.

I think the letters show us about how seriously these writers take writing, their own and the writing of others. How they agonize over getting words correct on the page…the letters show how carefully they read (and reread) others’ works, and favorites they returned to.

In the introduction, you note that Lucia joked their complete correspondence would have spanned many hundreds of pages. How did you choose from the trove of material?

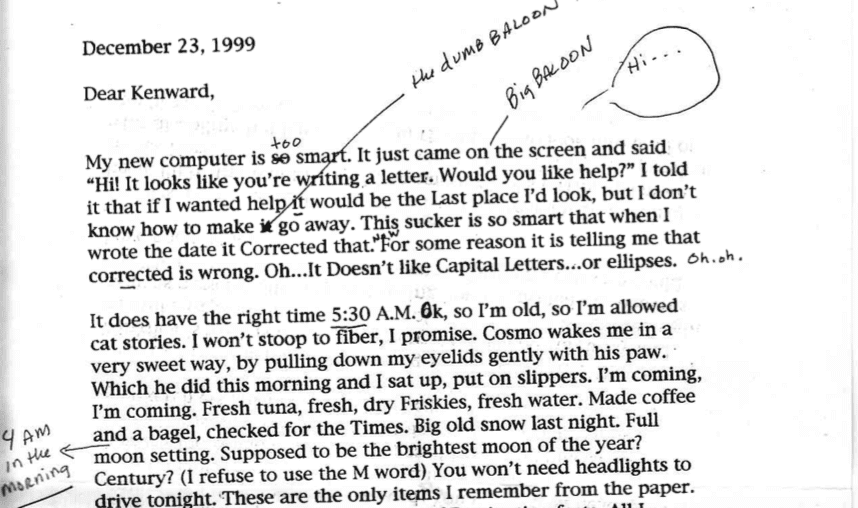

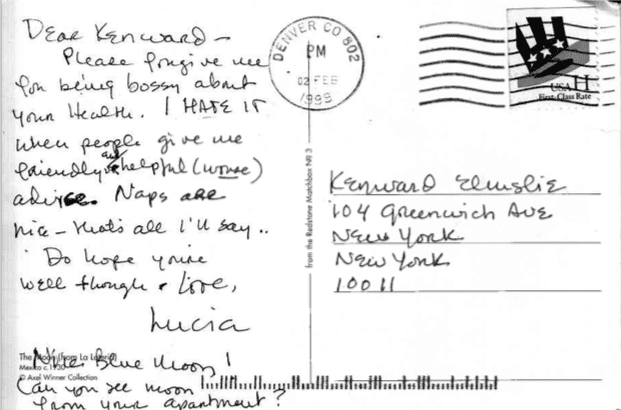

We compiled thousands of pages of letters (typed and handwritten), envelopes, postcards, collages, and clippings Lucia and Kenward had sent to each other, some in the guise of invented characters. The finished book Love, Loosha represents about 35 percent of the material. Selections were made mostly considering length (one letter from Kenward was 24 pages), but also at times considering how sensitive the material might be to loved ones, and considering how long the thread of the conversation continued over a series of letters, and how much might stand alone.

Was there anything you had to leave out that you think would be of interest to Lucia’s readers, or Kenward’s audiences and readers?

Certainly a lot of material, personal life and literary ephemera, had to be omitted for the length of the eventual publication, but I tried to include what most readers would find most interesting.

Did Kenward offer feedback on the publication?

Although Kenward was in favor of the correspondence being published (both he and Lucia loved reading other writers’ books of letters, and both of them collected postcards), by the time I began actually working on the project as a project/book, his health had declined so that he was mostly incommunicative. I did keep him up to date about the project’s progress, but he didn’t offer feedback or guidance. And of course, he unfortunately passed away June 29, 2022, just a few months shy of its publication.

How would you recommend readers find (or revisit) Kenward’s work now?

Many of his books remain in print. And his operas and musicals are occasionally still produced. The Poetry Project in New York and the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, both hold large archives of recordings of his readings and performances; some of his performances are on YouTube.

What might their letters teach us about literary community?

I think the letters show us about how seriously these writers take writing, their own and the writing of others. How they agonize over getting words correct on the page, and on the stage in Kenward’s case, and how they fretted when they were not actively working on something. The letters show how carefully they read (and reread) others’ works, and favorites they returned to.

Do you find letters richer than more recent modes of communication, say the emails and social media of writers today?

I think the handwritten and mailed letter is different in length and tactile quality than electronic communications, and certainly the idea of public posts versus private message has affected tone and content of epistles. There’s certainly a different quality and awareness of time associated with the mailed letter and the instant communication of a chat or email.

Has the experience of editing this volume influenced your own writing?

Not particularly, although I’ve thought of structuring a new essay in the form of letter excerpts, similar to Lucia’s short story “Dear Conchi,” but nothing directly influential. I’ve always been a fan of letters, and I’ve long been aware of the power of the epistolary form in fiction and nonfiction and poetry.

Can you say what your next project will be?

I have a new poetry book, Saints of the Republic, forthcoming in January 2023 from Spuyten Duyvil Press. I’m currently working on a collection of short stories and finishing a memoir of my years working in New York as Kenward’s assistant.

Chip Livingston is the author of five books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction and is a professor of creative writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He is a former fiction student and close friend of Lucia Berlin, and, upon Lucia’s introduction and suggestion, he became Kenward Elmslie’s personal assistant for ten years.

Lucia Berlin was the author of several short-story collections. In 2015 A Manual for Cleaning Women was published posthumously and became both a New York Times and an international bestseller. In 2018 Evening in Paradise, a second collection of her remaining stories, and Welcome Home, a memoir with letters, were also published to wide acclaim in the US and abroad.

Kenward Elmslie was a member of the New York School of poetry, having written fifteen books of poems, several plays, and a novel as well as opera librettos and the books and lyrics for Broadway and off-Broadway musicals. The grandson of Joseph Pulitzer, he founded the nonprofit small press and foundation Z Press, through which he provided professional and financial support for writers and artists.